I start my workshop on scientific grant writing by asking audience if they think a grant proposal should be more like a magazine or a newspaper.

What do you think?

The attendees are usually split about 50/50 on this one.

The ones that pick B want to pack in as much information as possible, but the ones that pick A already understand a key point of grant writing.

While yes, you need to convey the important information about your proposed work, you need to think of your proposal more as the magazine cover. Instead of giving the reader as many facts as possible, you need to:

- Catch and hold your reviewer’s attention

- Make it very easy to understand

- Be absolutely certain the reviewer cannot miss your key information

- Make it easy for your reviewer to sell your proposal to the rest of the committee

Even though each grant is a unique challenge (and each funding agency seems to want something totally different!), I saw some key errors that apply to any grant in my fall batch of proposals.

By fixing these often rather small points, the overall readability, impact, and appearance of the grant is instantly improved.

Interestingly enough, these key points could often be spotted instantly just by switching from a “newspaper” to a “magazine” mindset, and the fixes are often rather trivial compared to the work of putting together a research proposal.

So, with that, welcome to the Spring 2022 edition of biggest mistakes in scientific grant writing. Here are the top 17 scientific grant writing mistakes I saw repeated in this fall’s batch of applications and the fix you can employ to address each one.

They are broken down into categories based on if they related to:

These fixes are often very simple, so just keep reading and don’t stress if you notice any of these mistakes in your proposal!

And if you want more assistance than this, don’t worry, we have you covered.

You can go to my workshops page to check out when we will have the next scientific grant writing workshop to get specific help preparing and writing your grant proposal.

Reviewer-based mistakes in scientific grant writing

Check out the video on reviewer-based mistakes!

1. THE MISTAKE: Not thinking of your reviewer – Writing to maximize the information you want to say instead of what they need to read.

THE FIX: Think of your reviewer and have lots and lots of empathy for them. Like, tons.

My biggest tip for your grant proposals is this one, and really, all of the other tips I give you are just an extension or subset of this.

I think a lot of scientists never stop to think about who is on the other end of their grant proposal.

This leads to writing a grant that is optimized in our heads to have all of the information we think we need to include.

When I was a young scientist, I used to assume it was the job of the person reading applications to devote time to studying my application and finding the relevant information they needed in it…or, well, I at least never thought about it all that much, but would have thought that if I did.

I had no empathy for the grant reviewer – thinking only of what I thought I needed to say.

But, your reviewer is another person who has another full-time job and a family and is busy and overworked and stressed out.

They have a stack of grant proposals they need to read through and evaluate. They are probably behind schedule (because what scientists isn’t?), are exhausted, have a kid screaming in the other room because they have to do this in the evenings around their full-time job, and no matter how much they WANT to devote maximum brain space to your grant, their maximum available brain space is just not that much.

For more info on just who exactly reads your grants, check out this video:

So how to we write for really busy grant reviewers?

First, ask:

- Does the reviewer NEED to know this or do I just want to say it?

Before you add another technical term, abbreviation, or previous research, genuinely question yourself as to whether the reviewer actually needs to know this info or if you just think you need to tell it.

Will this technical term help the reviewer make a decision? Is it really that important?

This previous work you are describing – is it required? Can the reviewer make an accurate assessment of your work without it? If it IS necessary, can it be shortened? Maybe you DO need to mention that something was done before, but often, that is ALL you need – not an entire paragraph description of it.

Then ask:

2. Would I want to read this grant?

Every time you are shrinking line spacing to fit in more text or adding a complex figure or including a technical scientific term, put yourself in the shoes of your reviewer.

Imagine those looming deadlines, the lack of sleep, and the family wanting attention, and ask yourself if you want to read a grant with shortened line spacing or have to study a complex figure or need to deconvolute yet another scientific term.

Put yourself in their shoes, and then do everything you can to make their job easier. They will thank you for it, and your subsequent scores will thank you for it…because if you make it completely simple for a reviewer to understand and evaluate your application, it will be reflected in your scores. Promise.

Don’t believe me? You can always check out this post on how the language used in grant reviews can tell us what the grant reviewer was thinking. Usually, if they liked your application, they made it happen. If they didn’t like it, they found a reason to not recommend it – no matter how seemingly trivial.

2. THE MISTAKE: Making the reviewer read between the lines to find the key information

THE FIX: Make it obvious – Spell out exactly what the reviewer is looking for in its own subheading.

This section is especially pertinent for key parts of a proposal that the reviewer needs to look for. Think parts like:

- Broader impacts

- Interdisciplinary aspects

- Potential pitfalls

If you know that your grant wants you to include the broader impacts, make it literally impossible for the reviewer to miss the broader impacts…

My best suggestions for this in scientific grant writing:

- Make a specific subheading for that section

Even if it includes only a few lines, having the subheading makes it super easy for the reviewer to find that info when they are looking for it. More importantly, when the reviewer is arguing for your grant in the panel discussions, they won’t have to hunt for that information…they can go right to the subheading! - Include the exact wording where it fits: “The broader impacts of this research are…”

Where it doesn’t make the wording awkward, include the exact wording so that it is perfectly clear where this information is going to be. Seeing this key terminology can also “perk up” the reviewer and cue them to pay attention there in case their attention was flagging.*Note: This is NOT the same as meaningless statements like “This work is impactful” or “This work has a great impact on science.”

There MUST be specific content listed here, or this instead becomes a red flag!* - Consider formatting

I personally to see the pertinent information highlighted through formatting of some kind. It can really make your impacts or different aspects stand out to have them clearly italicized or bolded.

*The formatting can be especially useful for making it clear where you state your research objectives or gaps you are addressing.

3. THE MISTAKE: Making the reviewer study it – too technically detailed for easy comprehension

THE FIX: Ruthlessly sacrifice detail for clarity.

It’s a pretty common theme for scientists to want to pack as much info as possible into a proposal.

I mean, the more you know and the more information you provide, the better, right?

Well, not really.

If you spend too much time giving details that you don’t have the space to explain what those details mean and why they matter, then the details themselves are useless in the body of the proposal.

The details DO NOT MATTER if the reviewer does not understand their importance.

This is a very key point that I think many do not grasp – If you cannot explain why you are telling the reviewer something, you don’t need to be telling the reviewer that.

It’s that simple.

My advice?

Ruthlessly sacrifice needless detail for clarity of the detail you do include.

How will we do this in scientific grant writing?

- Cut anything we can’t expand on

This means that anything we don’t have the space to provide a “why” describing why that info is in the grant is probably excess info. If you don’t have the space to explain WHY you needed to tell that to a reviewer, you don’t have the space for that text.

Period. - Cut terms used less than 3 times

Use a term less than 3 times? You MIGHT not need that term at all. Can you instead replace it with the lay definition of the term? This can help simplify the text for your reviewer. - Cut surrounding text for terms used less than 3 times

If you don’t need a term, do you need the sentences or paragraph surrounding that term? Maybe its not just the term you don’t need, but actually everything surrounding that term. If cutting this text out still leaves you with a readable grant and answers all of the “why” questions for the remaining content, keep it out. - Ask yourself:

- Do I need this?

Make sure your answer explains WHY this part is important enough to keep and not just why you don’t want to remove it. - Is this clear enough?

- Can I explain it better or more simply?

- Do I need this?

Formatting-based mistakes in scientific grant writing

https://youtu.be/phBu7GX-6k0

4. THE MISTAKE: Writing a grant that no one wants to read

THE FIX: Make sure the entire grant is visually appealing and no pages look intimidating

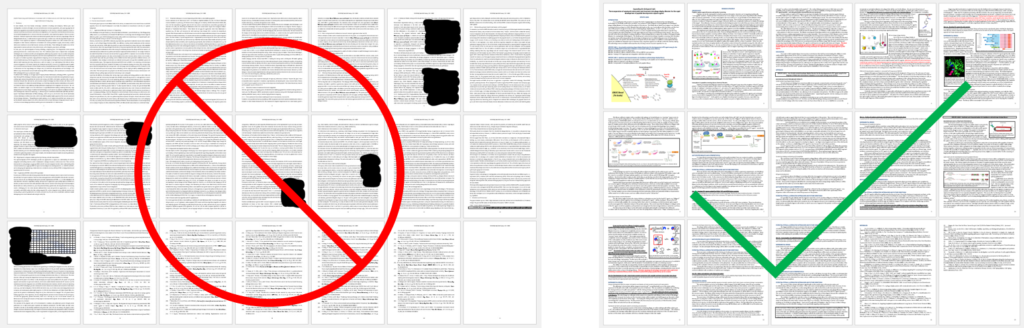

The best way to see where your grant might be losing readers is to zoom out in Word so you can see all of the pages of the grant on one screen. Which pages do your eyes naturally travel to? Its usually the pages with figures, bold headings, underlined sentences, colored text.

Are there pages that are nothing but plain text? Would YOU want to turn the page of a grant and see that?

When you are zoomed out, you can easily see the visual appeal of your grant.

Use this to make EVERY page visually appealing by following the next tips:

- Break it up into headings and subheadings

- Add figures that are easy to digest

- Add text formatting

- Change text colors

5. THE MISTAKE: Pages containing nothing but solid blocks of text

THE FIX: No blocks of solid plain text. That’s right – none.

You know the feeling when you turn to the next page of what you have to read, and it is a solid wall of text? That defeated sigh of resignation when you know you just need to buckle down and get to work on it?

Yeah, don’t make your reviewers have that feeling in your grant.

Keep tip #1 in mind always here…would you want to read this?

How to fix this in scientific grant writing:

- Break up this text for your reviewer.

- Keep it visually interesting.

- Prevent a reviewer from feeling reading fatigue as they flip to yet another page of text.

- Give the reviewer different things to look at or think about to help prevent them from drifting away or dozing off.

You can apply any of the following formatting tips to do this – and compare the “bad” versus “good” examples in the figure above!

6. THE MISTAKE: No figures

THE FIX: Add figures – a picture says a thousand words

It is true that pictures can say a thousand words. They can help make a point, do it in less text, and give the reader something to look at rather than more text.

Unfortunately, figures often get sacrificed when the writer has tons of text to add.

Use figures in your grant proposals to help show:

- how ideas or different parts of your grant integrate

- key plans you have in terms of flow charts

- how proposed technology will function

- preliminary results (*but see the caveat below)

- estimated future results – i.e., what would it look like if your proposal worked?

Essentially, consider adding a figure for anything where a visual aid might elevate the story you are trying to tell.

Adding figures to a grant proposal can also get a bit tricky sometimes, as the text should be wrapped around the figure, and moving the figure and caption together in Word can be a nightmare.

I have a post here for my preferred method for inserting figures – how to integrate the two in a textbox to save you some headaches.

Or you can watch the video here:

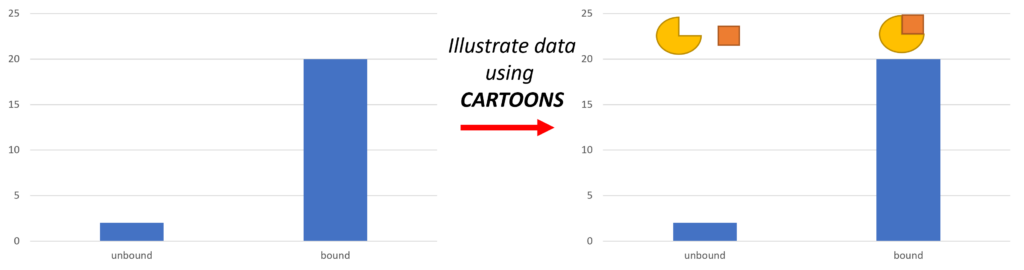

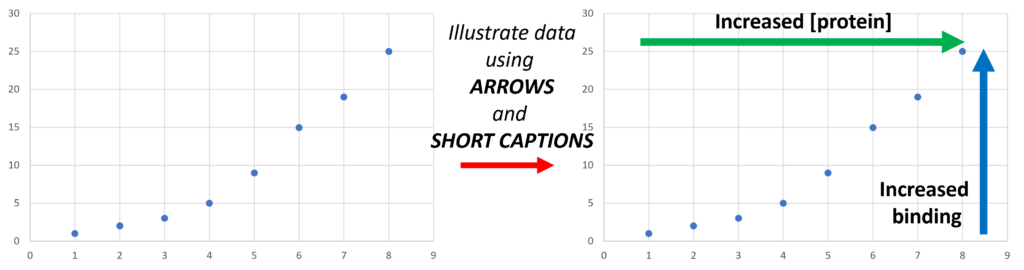

7. THE MISTAKE: Complex figures – anything that needs to be “studied” to be understood

THE FIX: Simplify all grant figures to be understood at a glance

What I DON’T want you to do when adding figures is add ones of technical results like what you might use in a paper. You DO NOT want your reader to have to study the figure AT ALL.

If your reader cannot glance at a figure and immediately understand it, it either needs edited for understanding or removed.

How can you edit a figure to increase understanding?

- add visual clues for the reader – showing a signal increase? Add an arrow with text that says “increased signal = increased binding”

- add a cartoon to explain what is going on

- remove anything extraneous or outside of what you are teaching the reader in this grant

- think about your figure as a magazine figure – flashy, bright, easily digestible.

Remember to think of your reader here and remember that it is NOT their job to study your figure and determine what it means. It is YOUR JOB to make it clear instantly.

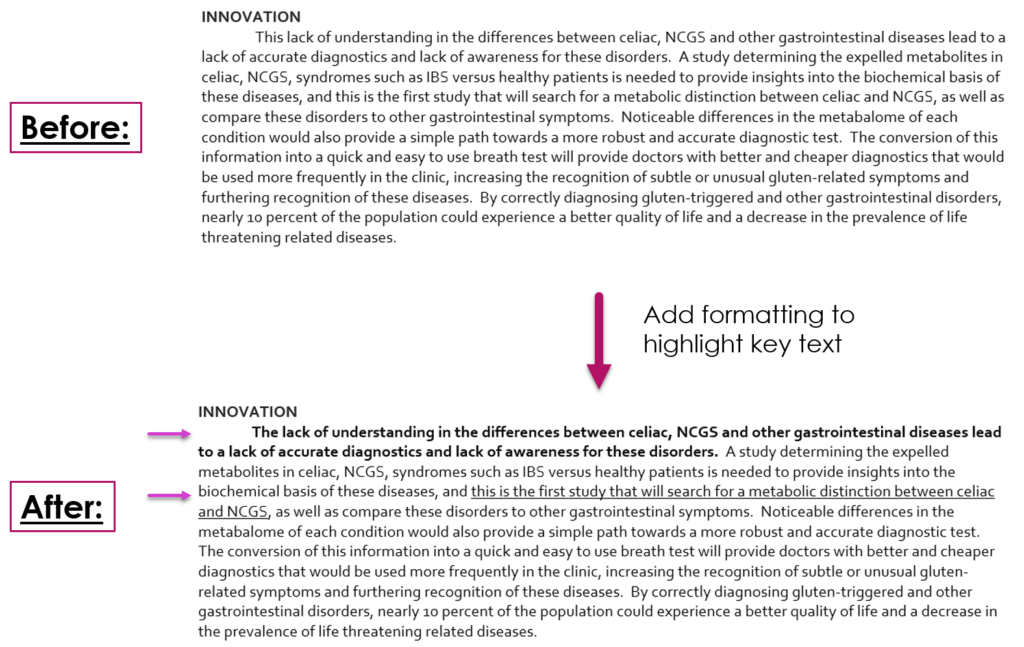

8. THE MISTAKE: Formatting into plain paragraphs like it is a research paper

THE FIX: Add formatting wherever possible – Formatting is your friend!

A great way to break up blocks of text is through text formatting. Think creatively here and use bold, italics, underline, and colored text to make different parts stand out to the reader.

Yes – all of this is allowed, and all of this is encouraged!

Formatting your text does a few key things:

- Breaks up blocks of text in your grant to make it easier to read

- Keeps the reader alert and focused on your text (it works! Try it!)

- Pulls the reader’s eyes to key information

- Makes it CERTAIN that the reviewer cannot miss your key points

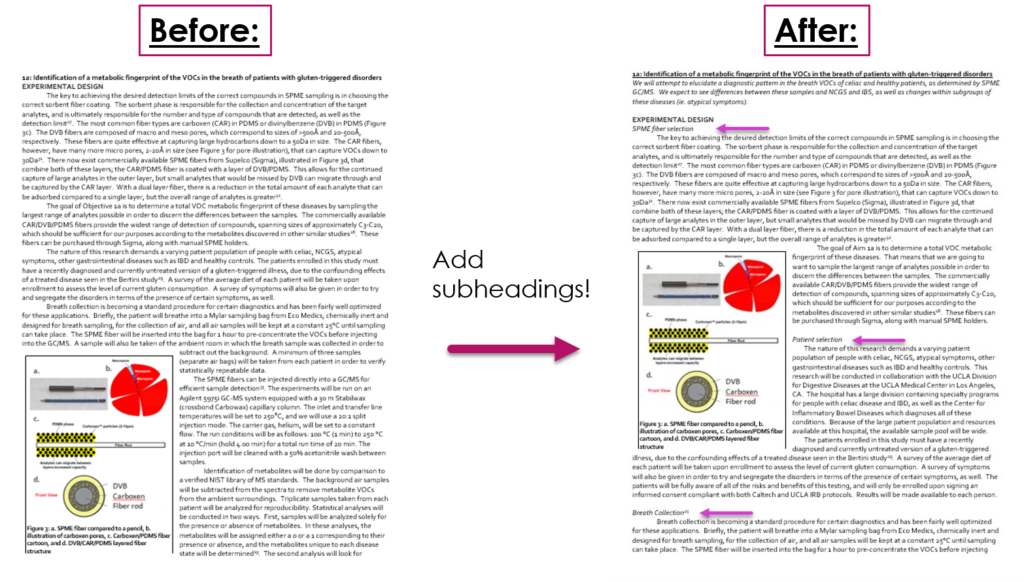

9. THE MISTAKE: Long sections with no breaks

THE FIX: Use headings to break up the text into smaller, easily digestible components

Often, the long stretches of plain text come in chunks of literature review where a few different topics need to be covered.

When this is the case, one of the best ways for breaking up the text is actually to split these topics into different subheadings.

It doesn’t matter if you have only one paragraph in the subheading – this visual difference makes for both a nice text break AND makes it very clear and easy for your reader to see just how many topics you are covering in the section.

Also, if they need to go back and review something, it is always MUCH easier to find with subheadings.

Content-based mistakes in scientific grant writing

10. THE MISTAKE: Too much information included!

THE FIX: Focus literature/previous work by writing only what relates to the problem addressed in the proposal

One of the most common questions I get is about how much to include in the literature/previous work section…

The answer? Less than you think.

It might seem crazy to you, the scientist, but the reviewer doesn’t actually care about what was done before or the state of the field – they care about how this contributes to the problem you are addressing in your proposal.

It seems subtle, but it means you want to spend less time giving facts and details and more time integrating the ones you do give into your idea.

How do you do this?

Focus your introductory and preliminary work paragraphs by deleting any that don’t specifically relate to this proposal…

- A description of the exact gap that is still remaining in the field after this work was done

- An exact explanation of how this work serves as a proof-of-concept for your proposed work

By doing this, you make sure every paragraph is relevant, because if it does not relate to one of those two points, it is not relevant to your proposal. Either the paragraph sets up what was previously done, but highlights where new work is needed or it lends credit to the proposed work you are going to do.

That is it.

Really.

And also notice a key point here – EXACT STATEMENTS for both of these points.

What does that mean?

Don’t assume the reader will see the gap because you laid out the previous work – they will not.

Make the gap or proof-of-concept statements super obvious:

- “However, this still does not answer…”

- “However, this method is not applicable in humans.”

- “, though this still needs to be tested in vivo.”

- “This means that [XXX aspect] of our proposal is likely to be successful.”

- “, meaning it should be possible to measure our proposed values using YYY technique [or in YYY scenario, etc.].”

11. THE MISTAKE: The need for your proposed work is unclear

THE FIX: Make sure the gaps in the field are apparent in EVERY PARAGRAPH

A common critique you might hear of your proposal is that the need for the proposed work is unclear.

This always sounds like daunting and devastating news when you receive it, but never fear, it is usually super easy to fix!

The main reason why the need for your proposed work is not obvious is because the proposal is lacking direct statements explaining where there is still a gap in the field and direct statements of how your work will fill that gap.

AND THEN…

Follow that statement with a relation to your proposal. i.e.,

“This issue will be address in Aim 1.”

Like I mentioned in the previous tip, we often think the relevance and gap is much more apparent that it actually is. Remember – our reviewer is not an expert in our field, so it is our job to spell this out for them.

By also following the advice in the previous tip, you can see how to add in these explicit statements. I usually also recommend a statement showing exactly how your proposal will address this.

For example:

“However, there is still no indication of whether this pathway is relevant in an in vivo setting. We will address this issue in Aim 2, where we will perform pulldown experiments and western blotting to look for pathway activation in prostate cancer cell lines.”

If you add statements like that in EVERY relevant paragraph, the need for your proposed work becomes immediately clear!

12. THE MISTAKE: Reiterating the problem at the end of the proposal

THE FIX: Painting the reviewer a picture of the world with your research in it

Just like I hate it when the conclusion of a paper is a summary of the paper, I also hate it when the end of a grant proposal is either a summary or reiterating the problem that was set up at the beginning.

The beginning of the proposal is for setting up a problem, the end of the proposal is for painting a picture of the world with your completed work in it.

The reviewer already saw the problem at the beginning, now show them what life will look like if you solve it.

How do you do this?

- Paint a picture – what will change with your research out there in the world?

- What will the world look like with your stated problem solved?

- Why should scientists be excited about the work that would come from this proposal?

- Why should non-scientists and lay-persons be excited about the work?

Your goal at the end of the proposal is to make the reader excited about funding your work. Don’t bring them down again by going back to the problem!

For more information explaining this, you can see the post I made on the conclusion of your manuscript. It is not quite the same as a grant, but there are still relevant questions here that might help you brainstorm what to write.

13. THE MISTAKE: Reviewer missed the importance of you work

THE FIX: Either better highlight gaps or how your proposal will fill those gaps

One of the biggest comments on a grant is that the importance of the work is missing. This is really similar to #10 above, where the need is unclear, and can be solved in similar ways.

Because most people manage to write a section detailing the significance or broader impacts of the grant, that is usually not the issue.

Instead, there are three major reasons why this is usually missing:

- Missing clear statements of the gap in the field

This is ALMOST ALWAYS the issue.

When the gap is not clearly stated, and it often isn’t, then it is almost impossible for a non-expert to see why your work is needed, and therefore, the importance.

–>To fix this, see mistakes #10 and #11 above. - Missing broad opening statements indicating the need for this field of research

This is usually the issue if gaps are clearly indicated.

If there is no broad statement at the beginning placing the work into a context your reviewer, who is not an expert in your field, would understand, it is very easy for that reviewer to miss the importance.

–>To fix this, see this post on writing the introduction of a research paper. The first paragraph here is similar in scope to what you want in a grant. - Never painting a picture of the world including your grant.

If the reader can’t envision how the world would look with your work in it, it is hard to also envision its importance.

–>To fix this, see mistake #12 above.

Detail-based mistakes in scientific grant writing

14. THE MISTAKE: NOT FOLLOWING THE INSTRUCTIONS

THE FIX: Read the grant call…and follow ALL of the instructions!

Unfortunately, every grant proposal is different, and each one will want something different and with a different submission instructions, page limits, formatting, etc.

As we specifically talk about the proposal in this post, we’re going to focus on the formatting, as that’s the biggest mistakes I see.

Your grant call is going to ask you for specific:

- page limits

- margins

- line spacing

- font

- font size

- etc.

These are NOT negotiations.

There is no arguing.

DO THIS.

Every year, I have someone send me a proposal and they think they are the first person to discover you can shrink line spacing and they are going to pull a fast trick on their reviewers.

You won’t.

As someone who reads papers and grants daily, I can see as soon as I open a document when line spacing is adjusted. Your reviewer will too, and line spacing is generally a set requirement in grants.

Changing this to fit more lines is NOT FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS and WILL get your grant thrown out unscored.

Don’t do that.

15. Overusing highly technical terms in scientific grant writing

THE FIX: Remove any technical terms that are not needed or used less than 3 times

Technical terms might fade to the background to you, an expert in your field, but they are new to your reviewer and can be a challenge to keep straight.

At the very least, all technical terms in your paper need to be clearly defined in lay terms to be absolutely clear to your reviewer.

However, to prevent your reviewer having to constantly flip back to your definition, I highly recommend removing any technical terms whenever possible.

Simplify the proposal as much as possible whenever possible.

How can you tell if you might want to cut out your technical term?

If you:

- use it 3x or less in the proposal

- can replace it with lay-terms

- can make your point using only the definition or explanation of the term

If you can do that, you have no need for the technical term and can remove it to simplify the proposal.

16. THE MISTAKE: Too many acronyms to easily follow along

THE FIX: Skip defining an acronym if you use it 3 times or less

Like technical terms, acronyms can also become challenging.

Many times, we are so used to using them we don’t even think about it anymore, OR we use them to cut down on the wording in our grant.

However, the more acronyms you use, the harder it is for your reviewer to follow your proposal.

Therefore, I recommend these tips for deciding if you should use an acronym:

- If it is a very long or complex term, then go ahead and use an acronym. Otherwise,

- Only if you use it 5x or more

- If you never have more than 1-2 pages between the definition and the next use (or else the reviewer can forget it!)

- Consider defining it again or reminding the reader if you have a chunk of the proposal that doesn’t use the acronym!

Need more help with your scientific grant writing?

And there you have it, my best tips and quick fixes for the most common scientific grant writing mistakes I saw in the latest batch of grant proposals.

Do you still want some more help? I also gave tips for fellowship applications in this post on Marie Curie Applications.

You can also go to my workshops page to check out when we will have the next scientific grant writing workshop! Or, even better, sign up to be notified the next time one is scheduled here.