There is one giant underused opportunity I see in a large majority of the papers I work with, which comes in the conclusion and final paragraph of the paper.

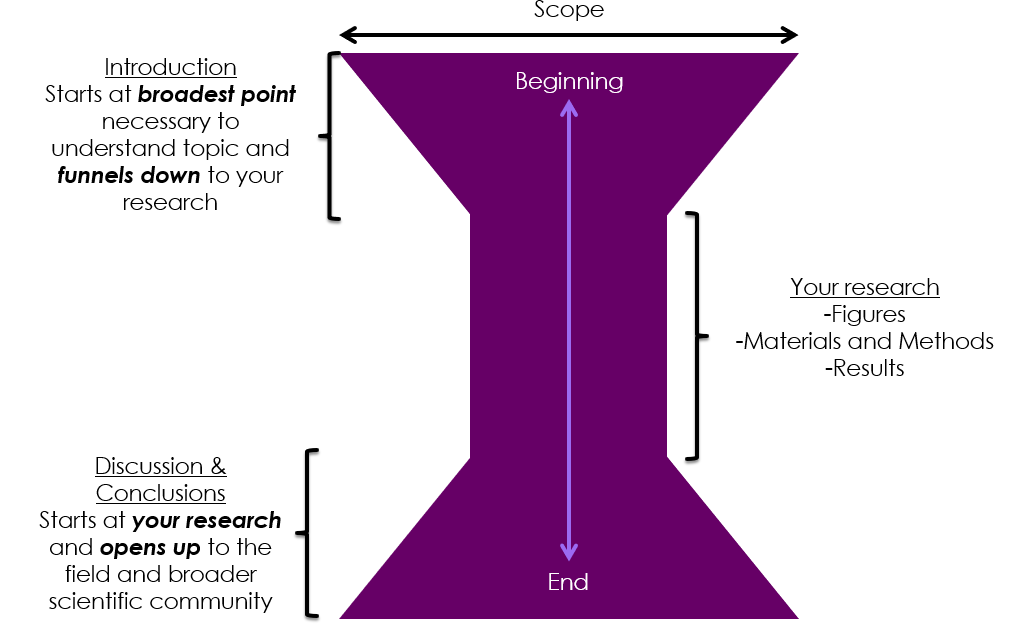

To see what this mistake stems from, lets first look again at the overall outline of a paper based on the paper scope (discussed in more detail in this post on writing order):

Looking at this figure, one can see that the scope of a paper should narrow out from the results section to the broader scientific community in the discussion. And the conclusion, being the last paragraph of the paper, looks to be the broadest section in scope.

Why, then, do so many conclusions contain nothing more than a summary of the research?

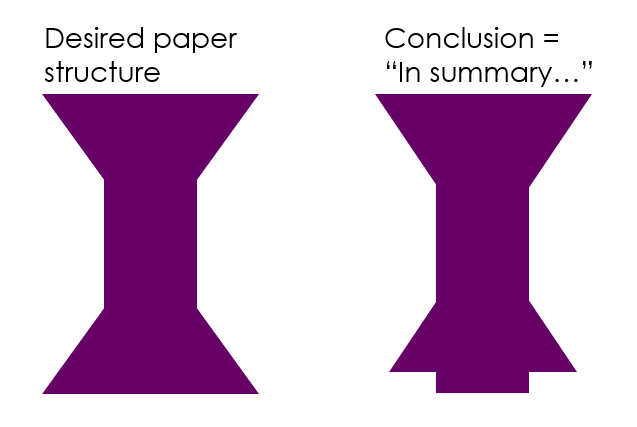

Setting up your paper for greatness by following the hourglass shape above can be derailed rapidly by ending the manuscript with a summary.

Why?

If the paper is done right, the discussion has the reader excited about the results of the paper and what possibilities are available for future research. The reader should be starting to make connections about the research, and start to see how this is fitting into the wide world of science.

Bringing them abruptly back to a summary of the overall paper abruptly derails that excitement and brings the reader back to a narrow focus.

And, lets be honest, if the reader gets to the conclusion of the paper, they likely stuck it out at least enough through the body of the paper to have an idea of what the overall highlights of your research were. Why does that need to be mentioned again?

Just look at a comparison of the scope graph of a desired paper and one with a conclusion of “in summary”:

So does this mean a paper shouldn’t have a conclusion?

NOPE!

It just means that the conclusion should never be a summary of what you did in the paper.

Notice I said “never”. I mean that.

Actually, one more time for the people in the back,

The conclusion should never, ever be a summary of the results of the paper.

There are a lot of “rules” I will give you that can often be broken when you need to in you paper. This, however, will never be one of them.

So what should a conclusion be?

Well, I am glad you asked!

Looking back at the figure of the paper structure, the conclusion continues out from the scope of the paper – looking even broader than that of the discussion.

That is because you want the conclusion to tell the reader why this paper deserved to be published and what it brings to the field,

which are the broadest categories in terms of scope that are in your discussion section.

Looking back at the post on the 6 keys to a good discussion section, what you really want to include in your conclusion are mostly the last 3 keys to a discussion, namely:

- Relate your results to the gap in the field

- Speculate beyond current knowledge

- Future directions

Including mostly forward-thinking points in your final paragraph leaves a forward-thinking impression in the mind of the reader. It highlights the importance of your work in the field and to science as a whole, and in this way, is also better suited to leave an impression that will make others want to build on (and eventually cite!) your work.

How can I write a more effective conclusion?

Still stuck?

The next time you are writing or editing your conclusion, try to answer any or all of these questions if they are relevant to your work:

- What specifically does your research to do advance science?

- What exactly does this bring to the field? How has it advanced the field?

- What can be built/done/made/calculated now that your research exists?

- How can your research be expanded upon in the future?

- Why might other scientists in your field be excited about this? How about non-scientists?

So how is your conclusion? Do you find yourself making this common mistake or do you naturally relate your results to the field at large?