It is not uncommon for the importance to be unclear in your scientific research paper or grant. This problem that comes in a lot of forms…

“Even though I KNOW my work is a good fit for the journals I am submitting to, I keep getting desk rejected from every one!”

“My grants NEVER get funded, but my colleagues who do similar work have tons of money.”

“The reviewers rejected the manuscript because they don’t see the importance of this work.”

“The reviewers/editors don’t see the impact of this work and are suggesting resubmitting to a journal with a lower impact factor.”

I know if you relate to this, you are probably struggling and frustrated and definitely don’t want to hear me say that my FAVORITE problem to fix is scientific manuscripts and grants getting rejected due an unclear importance.

It REALLY is though…

And the good news for you is that the reason for this is because the fix is so easy, and I can help you completely eliminate this from your manuscript and grant in this ONE post.

You are welcome.

Well, with that big claim, let’s get right into it…

Table of Contents:

WHY this happens – The main reasons for an unclear importance in your paper/grant

How to diagnose and fix each issue:

WHY this happens - Main reasons for unclear importance in your paper/grant

Implied versus directly stated points

Do you remember “The Dress”?

If you somehow missed this internet phenomenon, this picture of a dress was posted online, with about half of viewers seeing a white/gold dress and the other half seeing a black/blue one.

I still don’t know that I completely wrap my head around what happened here, but considering MY perception of its color has changed since I first saw it, I get it…

But the message here is that if we can’t get everyone to agree on something that is arguably as cut and dry as the color of a dress in a photo, why on earth do we think a reader is going to interpret technical scientific information the same way that we do?

And it is this point that relates directly to our science writing.

The biggest mistake I see writers make in their papers and grants is forgetting that readers are NOT US and won’t see the world in the same way that we do…

We write a paragraph that tells the reader some background in the field, and we expect that the reader will interpret that information how we did and see the issues in the field that need to be fixed AND the impact that fixing those issues would have.

However, this is NEVER true…

And why not?

Much like in this photo below of scientists examining an elephant, everyone comes in to your paper from their own angle that is both different from yours and probably different from what you would predict.

In fact, everyone brings their own:

- Biases

- Interpretations

- Background

- Experiences

- Priorities

…and each of these contributes to how we interpret everything that goes on in the world around us.

Which includes reading your science paper.

The people who read your paper will have a different knowledge bank to draw on than you.

They will have different priorities for what to focus on, including in YOUR work.

They will have different ideas about what matters and why.

Therefore…all you really need to know here is…

The reader will NEVER interpret text in the way that you want them too, so you need to spell out exactly what you want them to learn.

This leads first into the two main ways in which the importance can be “hiding” (i.e., important points that are often not clearly spelled out in scientific papers and grants):

- GAPS in the field that your work seeks to fill are not clearly and directly stated.

- The IMPACT/IMPORTANCE of your work is not clearly and directly stated.

Reader can't relate to your work

In addition to “hidden” unclear importance, we also miss one other key point about people when writing our papers and grants – no one has our same background and priorities.

Let’s talk about why this matters…

I had a student in a workshop who was writing a paper about developing new radar-based methods for studying bird migration, and he opened the paper with a statement to that effect.

So do you see the importance of this work with this statement?

I know I didn’t…

Why not? Because I don’t know anything about radar or bird migration. In fact, I have no idea WHY I should care about bird migration.

Does it affect me or my life?

IS THIS something that needs to be studied? Why? What will we learn from this? How will this affect the world?

This isn’t my field, none of my background helps me place this work into context to let me know how important it is, and I can’t even think of one single reason why we as a species would want to know that information.

So, what happens when I can’t see the importance of someone’s science?

I tend to default to THIS WORK IS NOT IMPORTANT because *I* can’t see why it is important.

And I am NOT the only one who does this. This is default for the human brain, meaning it applies to all of your readers. And the editor of the journal.

So how did we fix this with the bird migration paper?

Well, I finally asked a bunch of questions about his work, trying to get to the “why” behind why he was doing this.

We cycled through why’s such as “because this is important” and “because bird migratory patterns are cool!” (ARE THEY?!) before the “ah ha!” moment finally hit…

He just stopped and went “oh.”

And I knew he had it…

“We use bird migratory patterns to study the effects of climate change on bird populations.”

YES! There it is!

I know I’m going to hear it already – “…but not EVERY paper relates to climate change, and its stupid to try to make it fit.”

But here I want to counter with – if you don’t put your work into context for your reader, how will they know how to think about it, considering their differences in knowledge and priorities?

So no, maybe not every paper is curing cancer and reversing climate change, but that work is still operating in that particular sphere. And the reader needs to know what SPHERE to slot your work into when they are reading your paper.

Otherwise, how else will they see the importance?

Still skeptical?

Let’s draw this out.

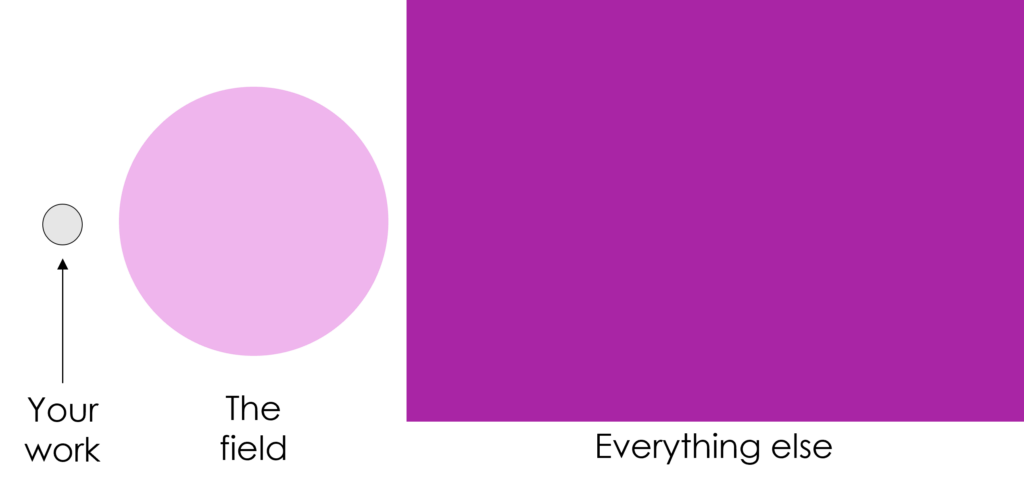

Let’s consider our research as this grey dot, our field as this bigger pink circle, and everything else as this purple box.

When we tell the reader what we did without placing it in context, we are handing them a puzzle. We are giving them our little grey circle and making them decide where it fits in the field and in everything else. We are telling them to judge how important our work is without telling them how it fits into these other spaces.

We leave it to the reader to guess where our research fits.

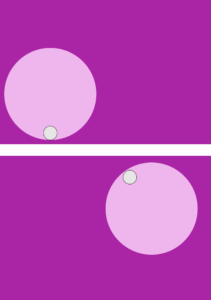

And in all likelihood, there are many different ways these can all be combined together.

For instance, maybe your work is at the bottom of the field and your field is in the bottom left of everything else.

Or, alternatively, maybe your work is located at the top left of the field and the field is located in the top right of everything else.

More importantly, maybe your work is VERY important in the first scenario, but the average work in the second one.

This means that if the reader is left to assume what you are doing, they might only know enough information to assume the second scenario, and they will think your work is NOT important or novel, even if you were aiming for the first scenario where your work is important and novel.

But if the reader doesn’t even know about the first scenario or doesn’t know to think of your work in that context, they will never see that.

–>I would NEVER have guessed that one could study climate change from studying bird migration patterns, even though it makes sense now that I DO know it.

So given that paper, I would never have known to think about bird migration in terms of something bigger like climate change and would be left wondering why we even needed other methods to study something that didn’t seem so important to me in the first place.

In this case, the unclear importance would have prevented me from understanding the need for this work.

And this takes us straight to our last two reasons why the reader misses the importance of your work:

3. The work is insufficiently related to the reader

4. The writing contains insufficient context for the reader to follow along

Phew, that’s a lot, I know, and we still haven’t covered how to know if you are making these mistakes and how to fix them…

So, let’s take these in order…

How to diagnose and fix issues with unclear importance

1. Missing: Direct statements of the GAP

How to include GAPS in the INTRODUCTION

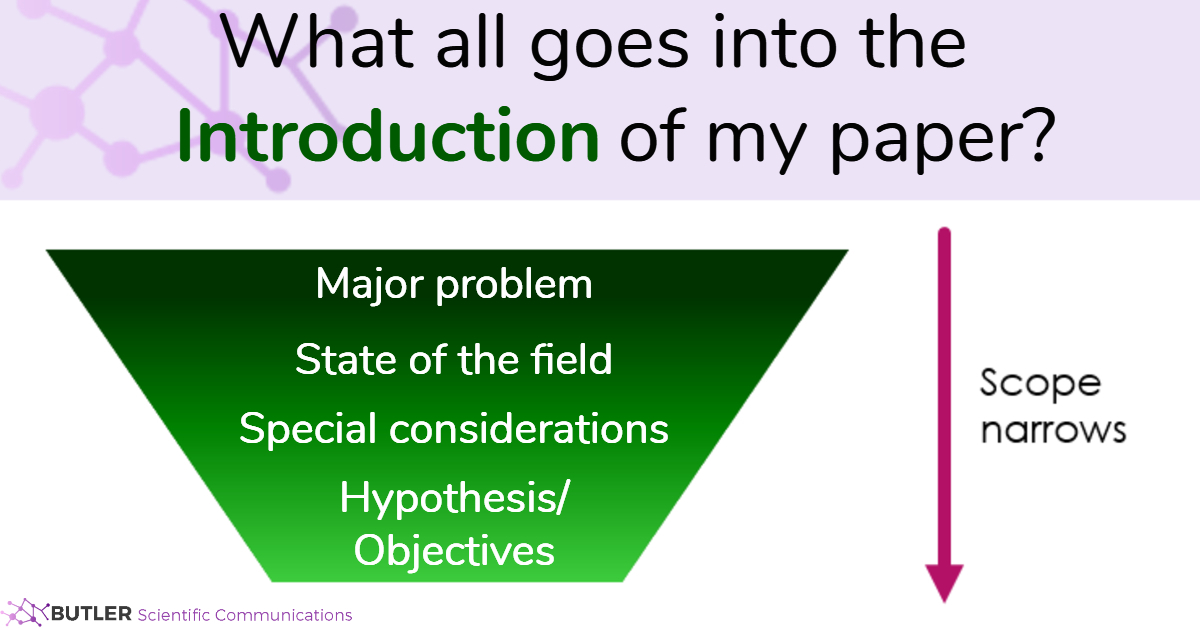

First, we’re going to look at our introduction to see if we are missing direct statements of a gap in that section.

I tend to start by coloring the introduction to break it down and see what I am working with.

For more on this, check these resources:

Or check out this video:

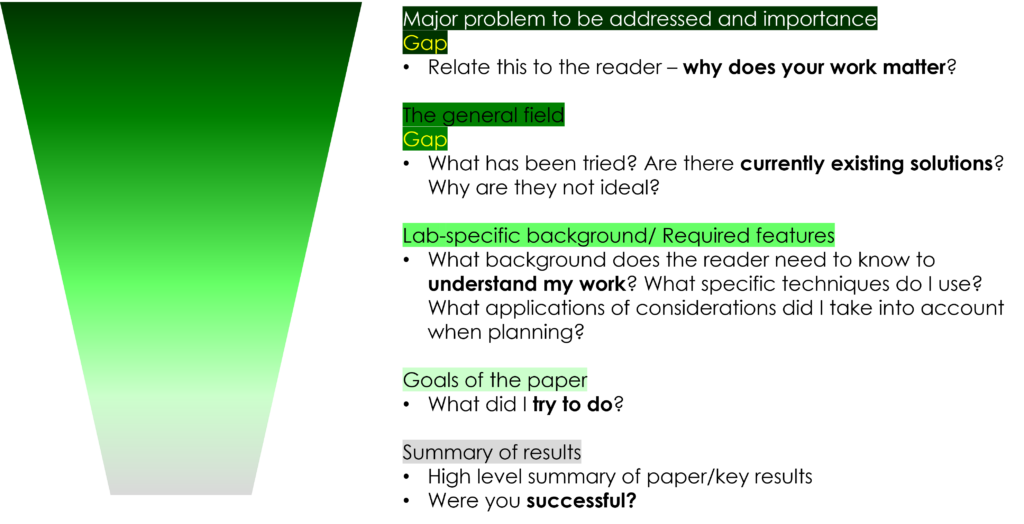

Otherwise, here are the key parts of an introduction and how they are colored.

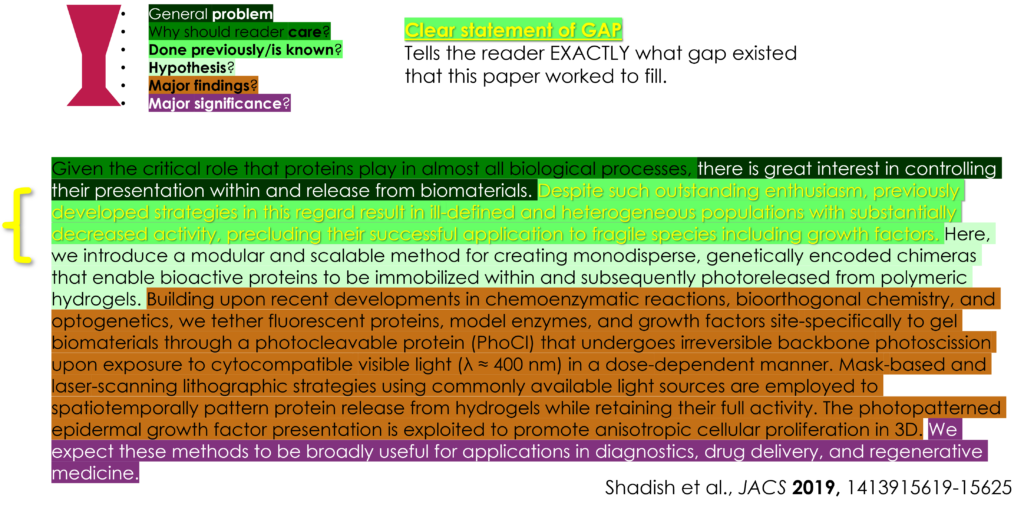

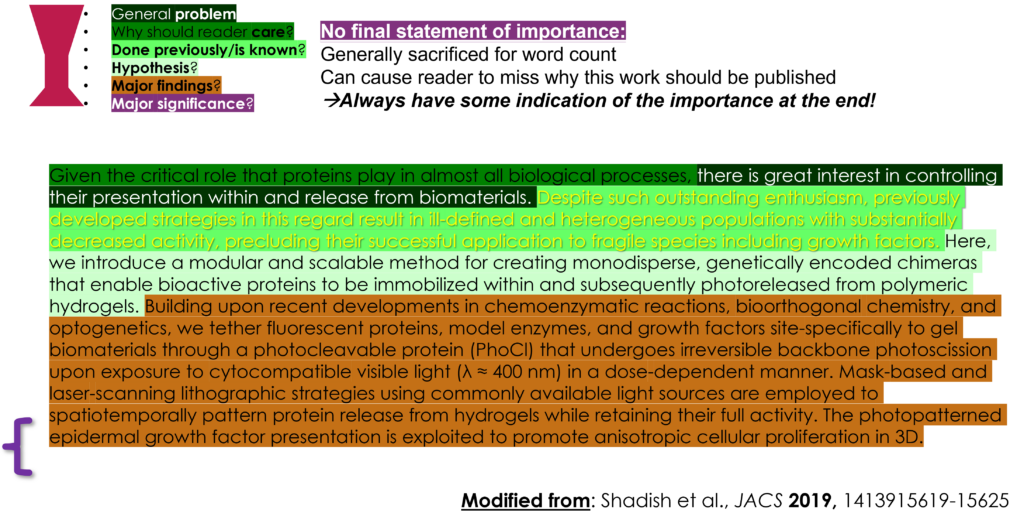

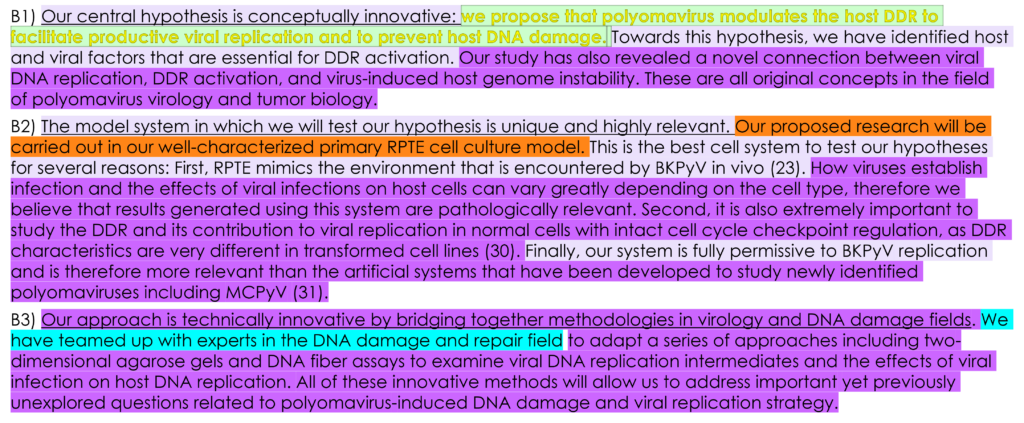

Note that the darker the color, the broader the scope it represents, which is intentional so you can see the flow of the scope as you move through a colored introduction. Note that the gap is indicated by yellow-colored text.

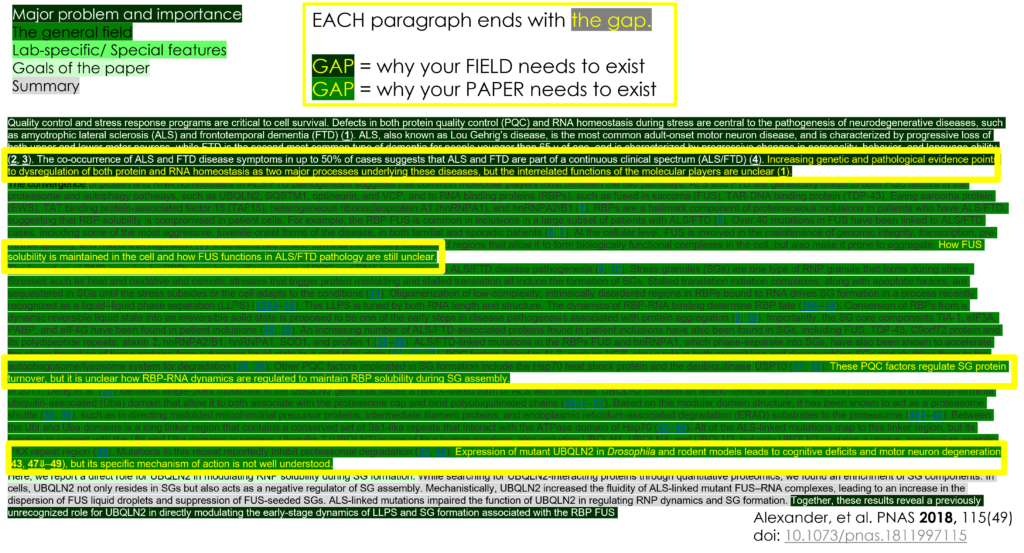

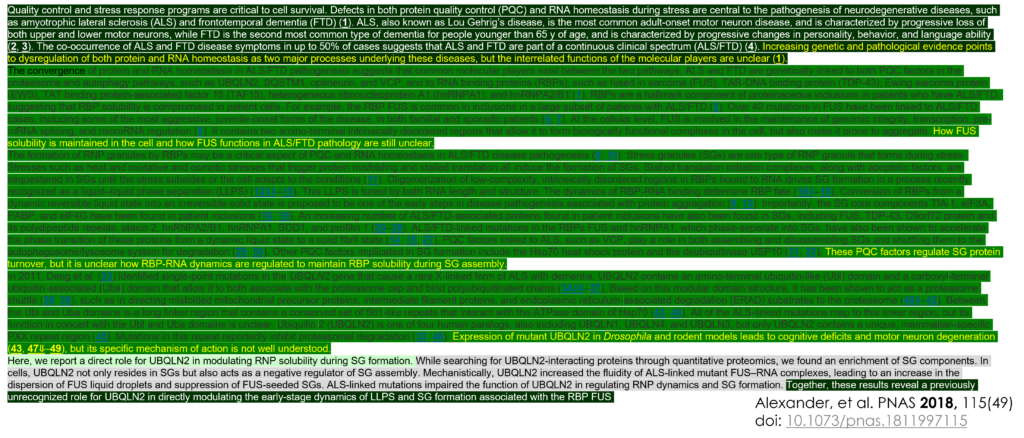

Then, here is a breakdown of a great introduction section, colored according to this color scheme.

You can see the flow of the scope as you move down the introduction, and you can also see direct statements of a GAP, as indicated by yellow text.

Intro from: Alexander, et al. PNAS 2018, 115(49). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811997115

The major thing I want you to see in this introduction is that EVERY one of the first paragraphs ends in yellow text – and note the wording of this text:

“…but the interrelated functions of the molecular players are unclear.”

“How FUS solubility is maintained in the cell and how FUS functions in ALS/FTD pathology are still unclear.”

“These PQC factors regulate SG protein turnover, but it is unclear how RBP-RNA dynamics are regulated to maintain RBP solubility during SG assembly.”

“Expression of mutant UBQLN2 in Drosophila and rodent models leads to cognitive deficits and motor neuron degeneration, but its specific mechanism of action is not well understood.”

Note how EACH of these paragraph endings is a DIRECT STATEMENT of where information is missing in the short description of the field that was included in that paragraph.

This makes it 100% certain that the reader will be able to see the GAP in the field.

If these gaps are missing, it is a sure sign that you are expecting the reader to interpret this for themselves – it sets up an unclear importance that is VERY difficult to decipher.

Action step:

“Color” your own paper, or just look for these DIRECT STATEMENTS of a gap.

Does your paper include these, or does it leave it up to the reader to interpret where the missing information is?

DIAGNOSE IT: Missing GAPS in INTRODUCTION

If you examine your own introduction using my coloring technique AND your gaps are missing, you will see NO yellow text.

Try reading your introduction without these gaps – do you see now how unclear the problem might be for a non-expert in your field?

Do you see how you can add in quick statements clearly telling the reader where these GAPS or problems are?

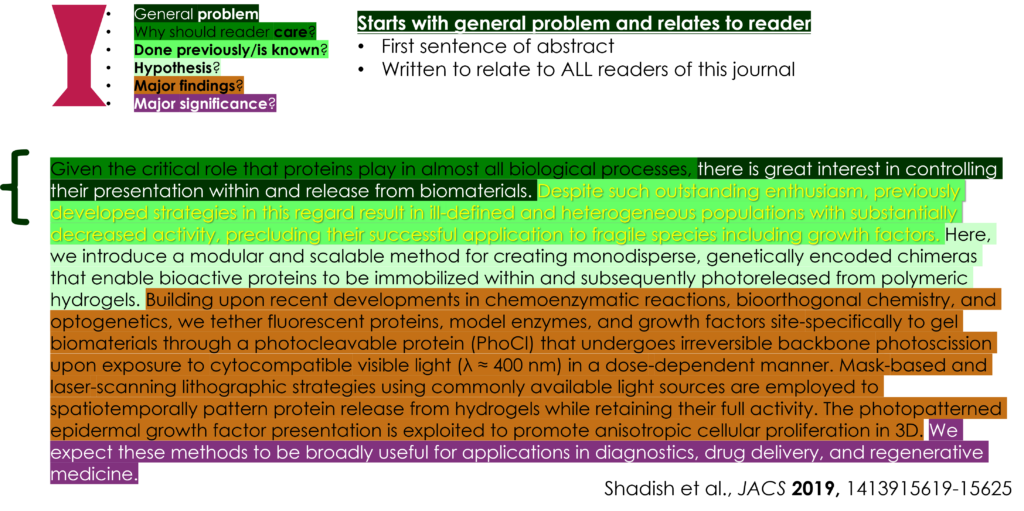

How to include GAPS in the ABSTRACT

The next place we want to look for a gap is in the abstract.

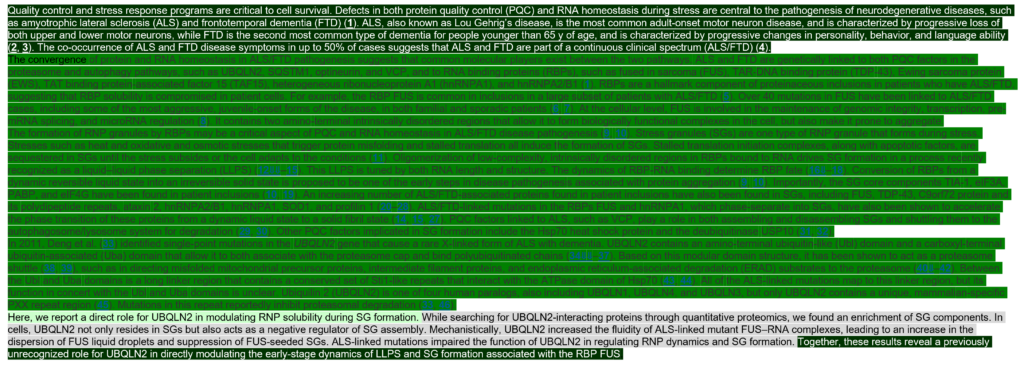

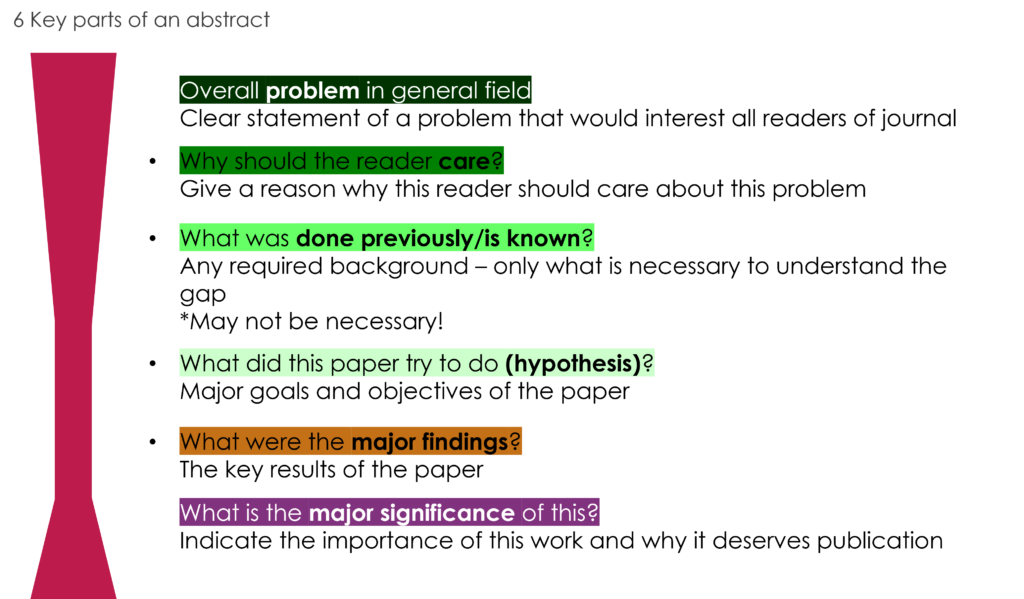

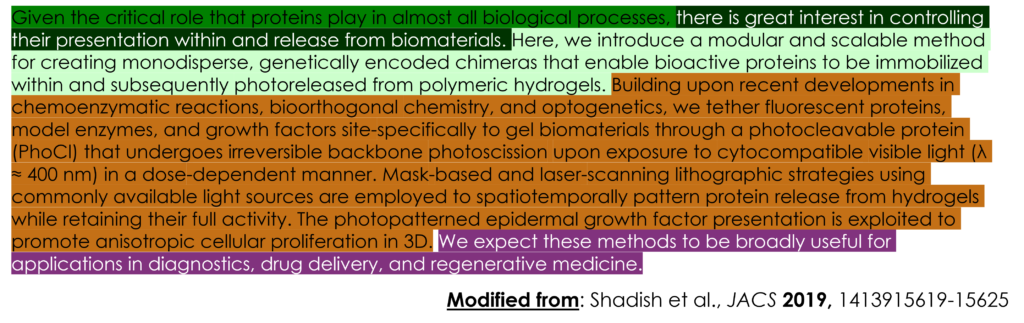

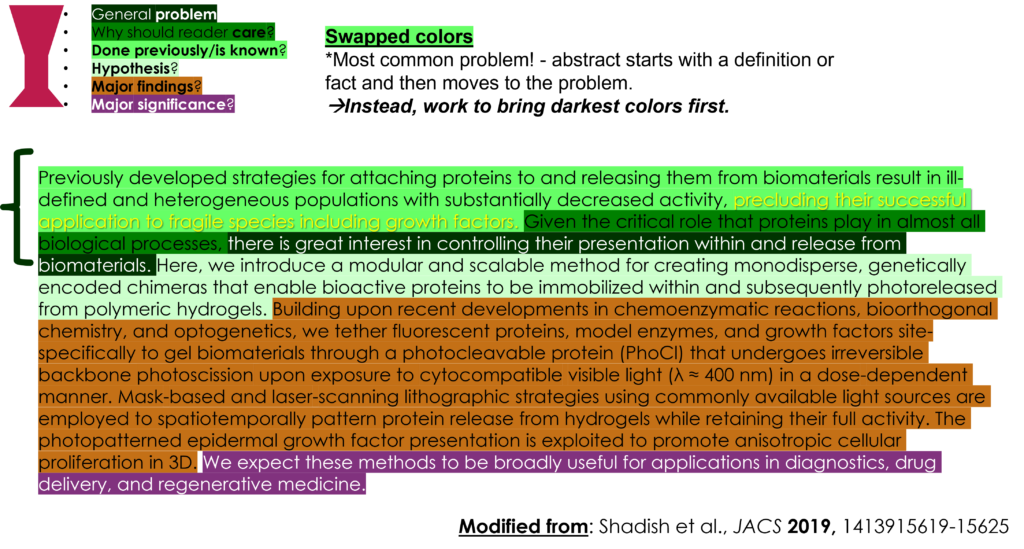

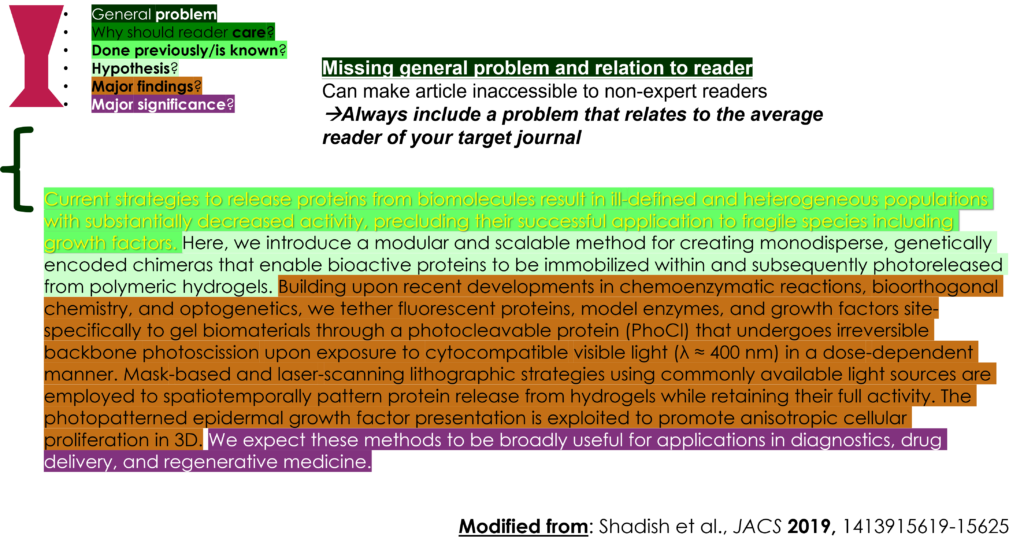

Similarly to with the introduction, I have colored the abstract to show the gap.

The colors are here, and you can learn exactly how to do this for yourself in detail from this free YouTube video or my Free abstract writing e-course.

Now we can take a sample great abstract, color it, and look for that gap as yellow text.

Again notice that there is a CLEAR, DIRECT statement of where there is a gap in the field that needs to be filled.

By stating this gap DIRECTLY, your writing requires no interpretation for the reader and ensures they will see exactly why your work is necessary.

DIAGNOSE IT: Missing GAPS in ABSTRACT

It is often easier for someone to see this in an abstract because the text is shorter. 🙂

So let’s check out what an abstract would look like if the gap was missing:

Now that you know what you are looking for, is it easier to see how much it negatively affects this abstract to have the GAP missing?

Can you see how this sets your paper up for an unclear importance?

Clearly articulating that gap is HOW the reader is able to judge how big or important of a step your work is.

How to include GAPS in GRANT proposals

Luckily here, grants function EXACTLY as papers.

Here, just like in a research paper, you want to look at your INTRODUCTION and ABSTRACT. They can be colored as presented above, with a goal of finding direct statements of a gap in EACH paragraph of the introduction and one sentence in the abstract.

FIX IT: Missing GAPS

Luckily here, typically once I get to this point and my writers SEE this issue in black and white (or yellow text!) they are easily able to see how to fix it.

This usually involves including a statement with negative wording, such as “but” and “however“.

Additionally, it might include direct statements of missing info, which will use terminology like “remains unknown“, “remains unexplored“, or “is unclear“.

Ideally, you want to ensure gaps are included in:

- Every paragraph of the introduction except the last (usually reserved for what was done in this paper)

- Any paragraph presenting introductory material, even if it is not in the intro.(i.e., need to introduce a concept in your results? Add a GAP here, too!)

- The abstract (can be termed “summary” or “cover page” in a grant)

For more resources, there are a few places you can look:

2. Missing: Direct statements of impact

How to include impact in INTRO and ABSTRACT

We are keeping intro and abstract together here, as this requires one sentence that is almost the same between the two sections.

Like I mentioned in the story about bird migration above, if the reader is not in your field, they likely don’t know the “so what” behind your work – why is this work being done? Why should they care?

For this, we want to look in two key places in our paper – the introduction and the abstract. Specifically, we are going to look AFTER we describe the problem, the research, and what we did…we want to use a statement of “so what” or, ultimately, “why does this work deserve to be published” at the end of each of these sections.

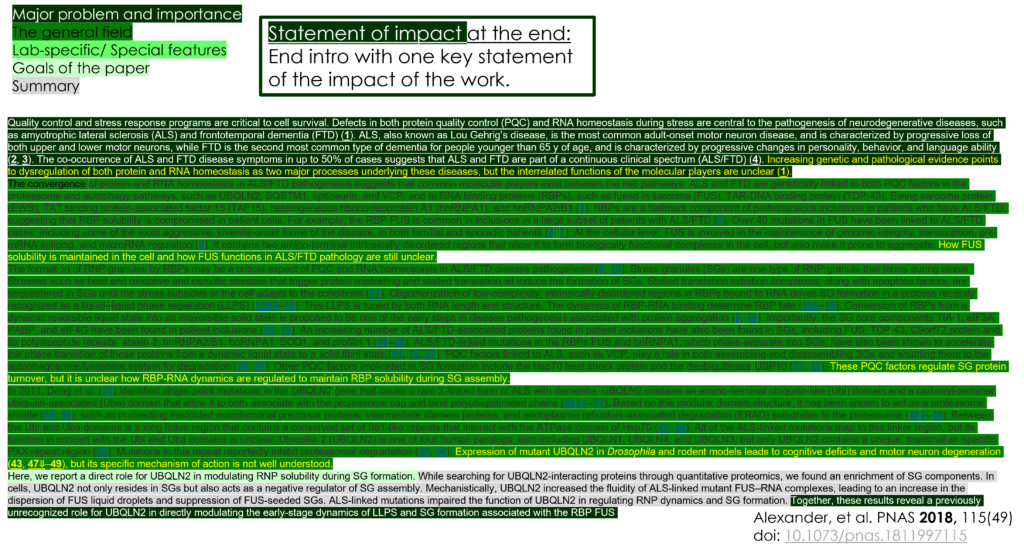

Let’s a start with that same introduction:

Notice here how the entire introduction moves from broadest scope at the beginning to narrowest at the end EXCEPT for the last sentence, which is back to the darkest color – and the broadest scope.

This sentence plays a key role in your intro – it is the sentence that tells the reader “so what” and “why this works deserves to be published.

Here is where the introduction is brought full circle, and one sentence shows the reader how the work you just discussed fits into the problems you brought up at the beginning of the introduction.

Basically, this is where you show HOW your work affected the field you introduced.

When stated directly and clearly, this is a direct statement of the importance of this work.

Now, let’s look at that same abstract again:

Notice here that the abstract ends in one sentence that is purple – here representing similarity to the conclusion of the paper.

Notice also how similar this sentence is to the last one of the introduction – it is going to be a very similar sentence, and it definitely should be located in both the abstract and introduction.

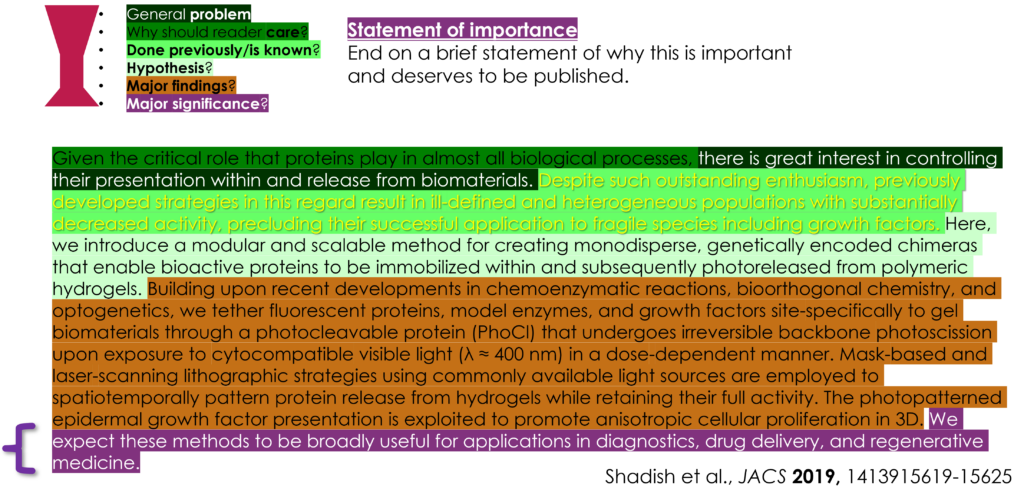

DIAGNOSE IT: Including sufficient importance in ABSTRACT and INTRODUCTION

So based on my coloring schemes above, let’s check our relevant paper and grant sections to see if we have sufficient impact/importance.

Starting with the abstract:

Hopefully when reading this abstract with no final sentence, it is obvious how important it is to have this final statement. Here is where you want to tell the reader exactly why your work is important.

I won’t show you another introduction picture, but it is the same concept there.

With that final sentence missing, the reader doesn’t get the story related full circle and the consequent reminder of WHY this work is important and deserves to be published.

How to include impact in the DISCUSSION

The next key place where we have an opportunity to directly state the importance of our work is in the discussion of our paper.

I won’t go into too much detail about the discussion section now because I have a free post on the site here and a video on YouTube that covers all of this!

There are two key places we are going to look in a discussion for statements of impact:

- The opening paragraph

- The closing paragraph (Conclusion)

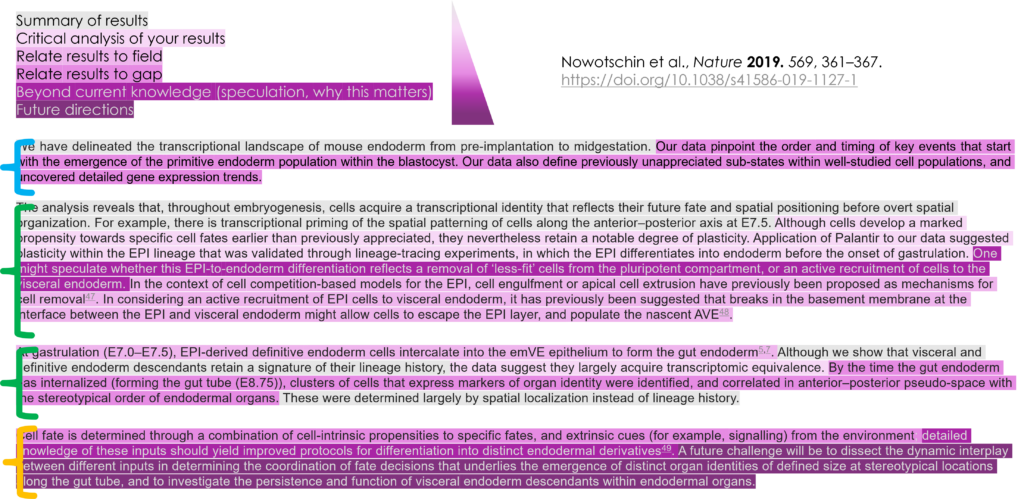

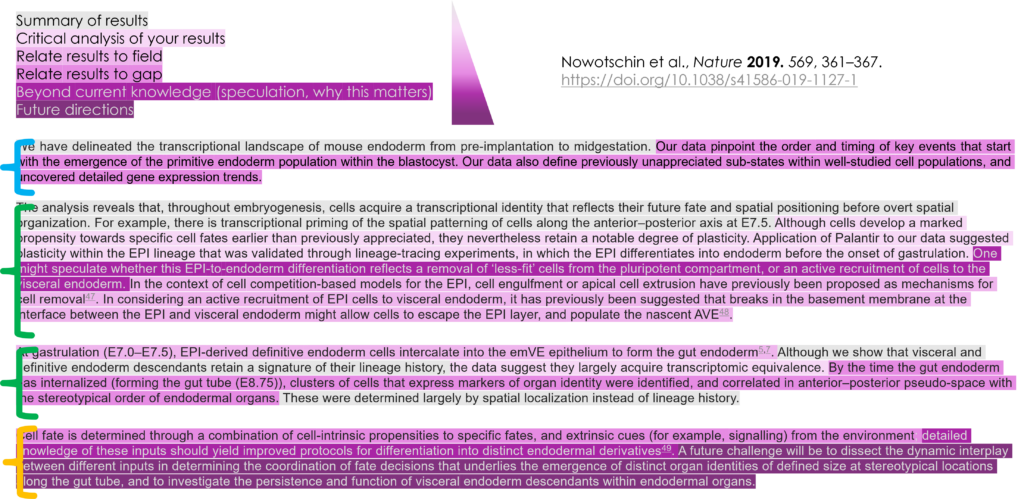

Check out this (short) discussion that highlights these two paragraphs (blue and yellow bracket) and what type of content is contained there:

(Discussion from: Nowotschin et al., Nature 2019. 569, 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1127-1)

–> Let’s start at the FIRST paragraph of the discussion (blue bracket in image).

Notice that here we have two main colors – a summary of the key work in this paper AND the gap in the field.

Noticing a trend (ahem – GAP)? 🙂 Hope so!

This first paragraph of the discussion comes right off the results of the paper, so it is a GREAT place to summarize the key points we want the reader to know. (Hint: a lot of people want to put this in the LAST paragraph, but read this post to see why I recommend not doing that!)

Here, using both a summary of our results and the gap, we can show the reader EXACTLY in clear words how our work helps fill the gap that was presented at the beginning of the paper.

Do you know what this is basically telling the reader?

You guessed it – EXACTLY why this work is important! And an ENTIRE paragraph (that is often missed!) dedicated exactly to doing that!

–> Next we want to look at that LAST paragraph of the discussion (yellow bracket in image).

Notice here that we have three main colors – the gap in the field, speculating beyond the gap (i.e., the unknown), and future directions.

With this paragraph, we are essentially painting a picture of the world now that our work exists. What can now be done or made or built or calculated because our research now exists?

Importantly – why should scientists and non-scientists be excited about this work?

Seeing the trend here, too? Good. 🙂

Because again, what we are doing in painting this picture is CLEARLY HIGHLIGHTING THE IMPORTANCE OF OUR WORK.

Perfect.

Want to know WHY we want these sections written this way?

Check out our video on discussions!

You’ll learn the logic behind structuring your discussion like this and the pitfalls to avoid!

DIAGNOSE it: Including sufficient impact in DISCUSSIONS

I have made this modified discussion (image below) to exemplify several issues I see in discussions:

If you remember the discussion above, you will see a few changes here:

- the summary is at the end of the paper

- the paper starts with a discussion of the field

- there is no forward-thinking paragraph

With these key things missing or in the incorrect place, it can be very difficult for a reader to judge the importance of your work.

Check your own discussion – do you have any of these same miscolorings? Can you see now how making this rearrangement can better highlight the importance of your work?

Can you use this to fix an unclear importance?

How to include the impact in GRANT proposals

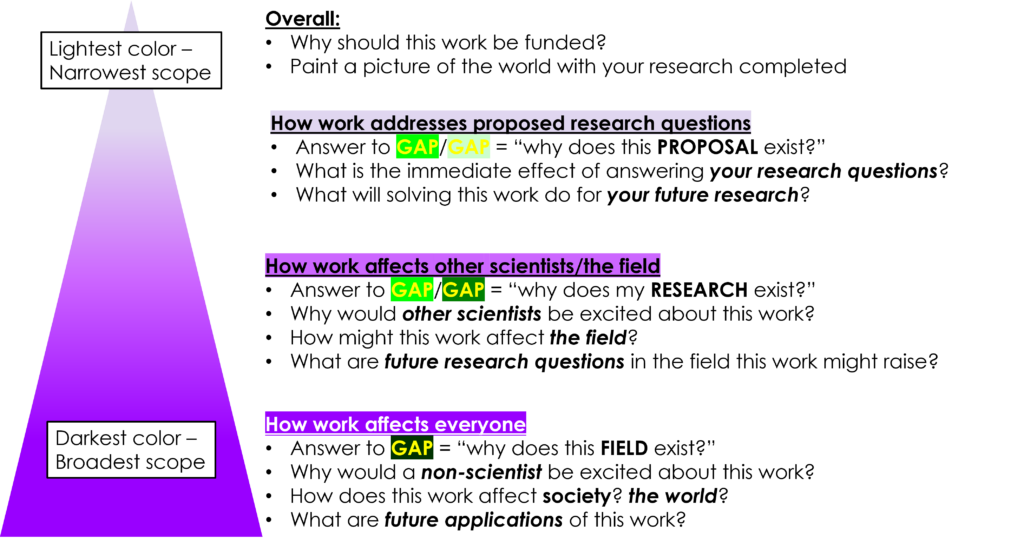

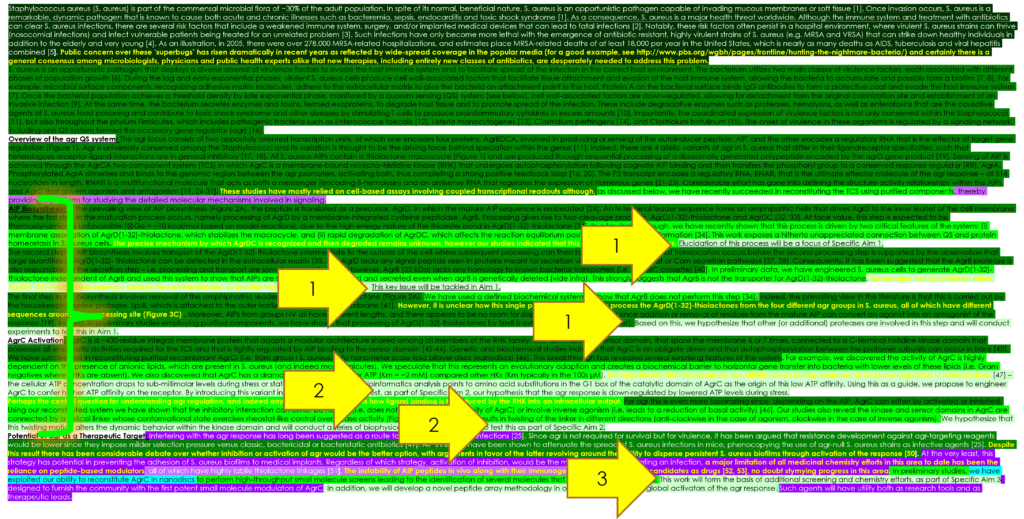

Here is the one issue with impact where we can deviate a bit from the other sections of a research paper, as grant proposals generally have a whole extra section just for talking about the importance of your work. So let’s make sure we get this right.

This section may have a few different names, but regardless of whether this is called “innovation”, “relevance”, or something else, let’s talk about what it means to convey the importance of our work in our grants.

First, let’s look at the parts of an innovation section.

Notice mainly what ISN’T included here – no background, no summary of proposed experiments, etc. All of the points we want to include here directly relate to how this work will address research questions or affect other scientists, the field, and society in general.

Now let’s look at the impact section of a grant colored according to this scheme.

Note that these sections are generally quite short – 0.5–1 page is all that is needed!

Notice here what we don’t see (or much of) – introduction or details about the proposed research plan. This section is reserved for discussing what is innovative – or in other words, what is IMPORTANT.

Here, the writer also covers the two first points of the impact – how this work answers the immediate research questions and how it affects the field as a whole. In this particular grant, the last part, how this affects society, is included in the significance section.

The main point here is to make your innovation section FULL of actual IMPACTS and INNOVATIONS.

Don’t dilute this section with lots of introductory text or research plans and let the importance slip by unnoticed.

And finally we have one more important point to cover here for grant proposals –

Just because a grant proposal has an impact/importance section does not mean that is the only place the impact/importance should be highlighted.

^Go back and read that again. Its that important.

Basically, yes, your proposal likely has a section specific for highlighting the importance of your work, BUT AT THE SAME TIME, everything we just covered for the intro, abstract, and conclusions of a research paper should ALSO be covered in your grant proposal.

Therefore, in ADDITION to the impact/importance section, you should include this in:

- the abstract (or summary, cover page, etc.)

- the introduction

- the conclusion

In general, my advice here is the same for the above sections of a research paper (i.e., include EXACTLY as in the intro and abstract/summary part; go back up to read those!) with one small addition –

In the introduction, follow ALL statements of a gap with a statement of HOW THIS PROPOSAL WILL ADDRESS THAT GAP.

Check out this sample proposal to see what I mean.

(Sample NIH R01 grant; PI: Muir, Tom; https://www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2-R01-AI042783-16A1_Muir_Application.pdf)

Notice here how the introduction doesn’t just end on the yellow text of the GAP.

Every statement of GAP is followed DIRECTLY by how this proposal will address it and/or where it will be addressed (what aim).

“This will be addressed in Aim 1.“

This short addition to the intro of your grant proposal can go a VERY long way to directly connecting your aims to the problems in the field.

Hey guess what that shows? THE IMPORTANCE of your proposed research!

DIAGNOSE IT: Including sufficient impact in GRANT PROPOSALS

Now let’s cover how to diagnose an unclear importance in your own grant proposals.

There are two ways that your innovation section might look after being colored that would indicate an issue in properly structuring your innovation section.

As per the other sections, these are examples that have been modified from the original text to reflect the most common problems I see – the authors are not to blame for this!

For the first, what do you see here?

Hopefully this is clear, and you can see that when the first point is dominated by introductory material, there isn’t much space to expand on the actual innovations.

I see this mostly when the introduction is not properly set up – writers often use this section to include the gaps in the field that SHOULD be included in the introduction section.

If your introduction is set up correctly, you should not need introductory text here. If you are finding introductory text, you likely need to move that to your introduction instead and review the section on including gaps in the introduction.

Here is the other most common issue I see here:

Note here a related problem – the point of innovation is dominated by WHAT will be done in this grant, taking away from what is innovative.

If the research methods or techniques are the innovation, that is absolutely fine – but instead of repeating the research plan, STATE DIRECTLY that the methods are innovative along with WHY they are innovative.

You do not need to repeat details of the method.

This will go much further towards conveying the importance than summarizing parts of the research plan and making the reader interpret for themselves where the innovation lies.

FIX IT: Including sufficient importance

–>Fixing importance in Abstract and Introduction

In the abstract and introduction, it is as simple as adding one sentence at the end of each that DIRECTLY states that importance.

–>Arrange your Discussion to make your importance clear:

- Start with one paragraph that is (i) a summary of the key results of the paper directly related to (ii) the gap in the field this work sought to fill. This tells the reader EXACTLY how YOUR WORK affects the FIELD…i.e., the importance!

- End with one paragraph that includes (i) how your work addressed the GAP, (ii) what new hypotheses or speculations can you make now, and (ii) future directions.

- Ensure that every point in your innovation section is solely discussing the importance of your work and WHY it is important – no repeat info from other sections.

- Follow all instructions for including importance in the ABSTRACT, INTRODUCTION, and CONCLUSION of a research paper – these are the same! (Though CONCLUSION of your grant MAY come at the end of the Significance statement in an RO1 – effectively at the end of the INTRO)

- Include a statement after each mention of the gap in the introduction that states EXACTLY how this proposal addresses that GAP.

Luckily, writers tend to be able to compose the “importance” sentences once they just realize WHERE they are missing from their work.

If you want a little help figuring out what exactly to include here, though, we have you covered!

Brainstorming your IMPORTANCE sentences:

(Last sentence of ABSTRACT and INTRODUCTION and FULL CONCLUSION PARAGRAPH)

- What specifically does your research to do advance science?

- What exactly does this bring to the field? How has it advanced the field?

- What can be built/done/made/calculated now that your research exists?

- How can your research be expanded upon in the future?

- Why might other scientists in your field be excited about this? How about non-scientists?

Overall for these sections, you want to remember to PAINT A PICTURE of what the world looks like now that your work exists…there is no better way to convey importance!

Use these questions to brainstorm what to include in your own paper, and if you are still stuck, here are a few places you can look:

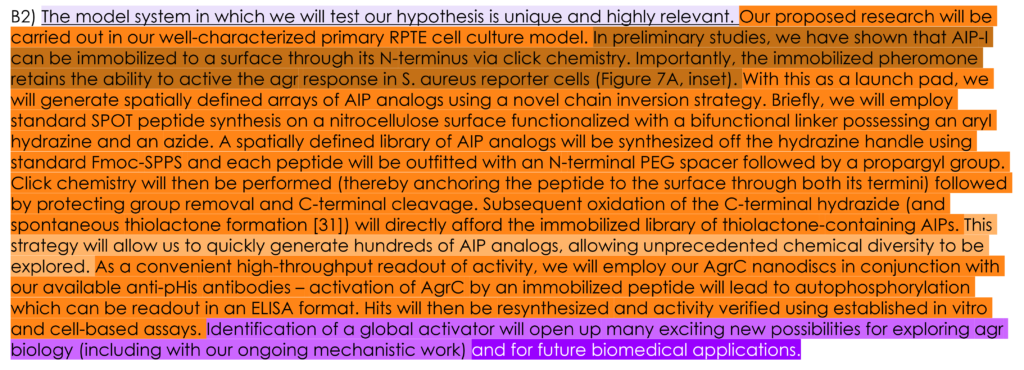

3. Work is not sufficiently related to reader

How to relate to a reader in Abstract and Introduction

The first place we relate to our reader is through our abstract and then directly through our introduction, so let’s start at the abstract.

Remember the story about the radar-based methods for detecting bird migration? Remember how important it was to be able to place that in context?

Let’s check out this ideal abstract that does a great job of relating the field to the reader:

Notice that the VERY FIRST SENTENCE here starts with a problem general enough for the average reader to relate and tells them why they should relate.

Perfect!

Now your reader knows how to place your work in context. Aka. how to tell if your work is important!

We can do the same thing with the introduction:

Notice this introduction starts at that broadest scope – the major problem a reader can relate to.

This is the paragraph where you actually explain why your FIELD of research is important.

This is here you show your reader where the pink circle of your field fits in the bigger picture of everything else. Here is where you tell the reader WHAT puzzle you are building.

THIS is what tells a reader why they need to care about this project.

Remember – end this paragraph on a GAP statement! This GAP should be the reason your FIELD of research exists.

DIAGNOSE IT: Relating to reader in ABSTRACT and INTRODUCTION

Based on my color schemes, let’s first check the abstract for sufficient relation to the reader:

Notice here how different the abstract is when the part that relates to the reader is buried after a definition.

My suspicion here is that if you don’t have a solid reason for reading this paper AND it is not in your field, you don’t get much further than the first sentence. It is going to seem irrelevant for you unless you are directly in field.

It is common to start an abstract first with a definition of statement of the state of the field, but keeping in mind our points in this post, notice how this can lead to unclear importance.

Now let’s look at another way in which an abstract might be incorrectly related to the reader:

Here our problem starts similarly to above, by starting the abstract on a key issue in field without firsrt relating to the reader. However, while the above example at least eventually did this, this abstract skips that altogether.

Here, let’s again focus on having a broad statement at the beginning that places this work into context for your reader and gives them something they can relate to while reading your paper.

Your work is only going to matter as much as you can convince others that it does. If you can’t convince a journal editor to publish in a good journal, less people will see it – so work to make your research relatable.

How to relate to a reader: Conclusion

Next we want to look at the conclusion, because another great place to really hammer home the importance of your work is in the last place people will read.

Make sure that last impression of your paper is full of why your work matters and deserves to be published!

Let’s remember how we did that in our discussion using colored text:

Notice how instead of being a summary, the final paragraph is very forward thinking – highlighting how this work can affect future work, projects, and future directions that can spin off from this work.

This helps show that your work isn’t being done in a vacuum and that it is going to affect the field and the world at large (if possible for your particular project).

If you can show how your work affects the field or the world, you have shown the importance.

DIAGNOSE IT: Relating to reader in CONCLUSION

Here we can look at the exact same problematic discussion as I showed before:

Here again, having the conclusion be a summary of the work does a huge disservice to conveying the importance of your work.

Why?

Because instead of showing the reader at the end of the paper HOW this work might relate to them or other scientists or the world, this discussion closes in on itself and repeats what was done.

While useful to have a summary, we instead want this ending to be BROAD in scope.

Open this up for your reader.

PAINT A PICTURE of the world with your research in it to highlight this importance.

Look for darker colors at the end of your discussion. If you see anything else instead, try to rearrange to make it so.

How to relate to a reader: Grant proposals

Again here, highlighting the importance in sections that are also contained in grants should be treated in the same way – meaning we want to look at the ABSTRACT, INTRODUCTION, and CONCLUSION of our grant in the same way as for a research paper.

Do we have sufficiently broad information here to attract and hold a reader’s attention, and do we provide enough forward-thinking information in our conclusion to relate our work back out to the field and society as a whole?

These issues are diagnosed and fixed exactly as for research papers.

FIX IT: Relating to the reader

Brainstorm with the following exercises (details below):

- Incessantly ask yourself WHY to get to your BIGGER PICTURE

- Brainstorm the answers to forward-thinking questions

–>Incessantly ask yourself WHY (i.e., pretend you are a small kid!)

Let’s go back to that story of the radar-based methods for studying bird migration and examine how me and the student got to our why.

Here, we are going to keep asking WHY until we have that “ah ha!” moment that tells us we hit the point that our readers are going to relate to.

Student: “We need to develop a new radar-based method for studying bird migration.”

Me: “But why do you want to study this? Is that important?”

Student: “Well, yes, because its important to study bird migrations patterns.”

Me: “Is it? But why?”

Student: “Because bird migration patterns are cool!”

Me: “…are you sure? To everyone? Why are they cool? What do you learn from them?”

Student: “Oh…well…you learn about the effect of climate change on species biodiversity.”

Me: “There it is!”

See here how I kept asking why until even the student realized he hit on the point he needed for this paper. Now the reader will know how to place his technology in context, showing then WHAT context to put it into.

- What specifically does your research to do advance science?

- What exactly does this bring to the field? How has it advanced the field?

- What can be built/done/made/calculated now that your research exists?

- How can your research be expanded upon in the future?

- Why might other scientists in your field be excited about this? How about non-scientists?

For more info, you can check here:

4. Results lack sufficient context for reader to follow along

How to include sufficient context in RESULTS

Without sufficient context in your results explaining to your reader WHY you did certain experiments, details about those experiments, expected results, etc., your reader won’t be able to follow along.

Including sufficient context in your results ensures that your reader can:

- Follow you LOGIC throughout the paper

- See WHY you did each experiment (and not a different one!)

- Be more INVESTED in your “story”

Conversely, when a reader DOESN’T follow our logic, they naturally give less weight or importance to what we did in our paper or what we are proposing in our grant.

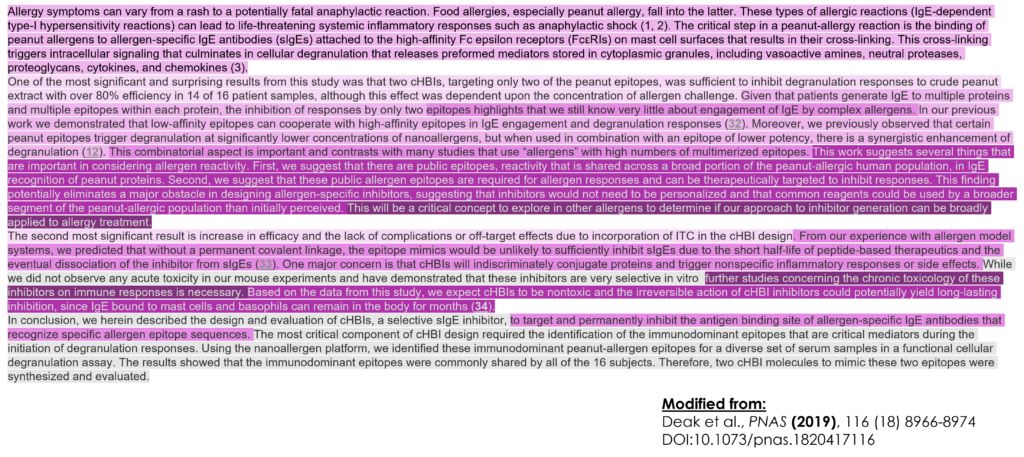

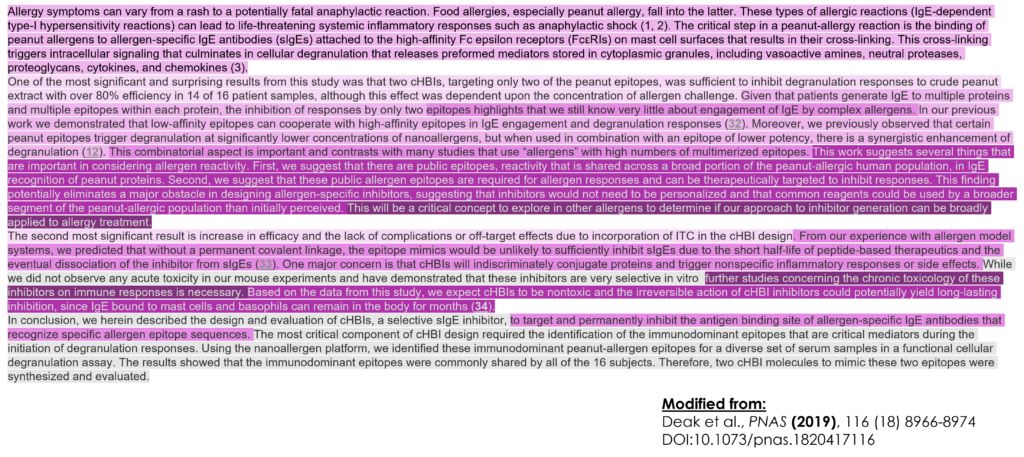

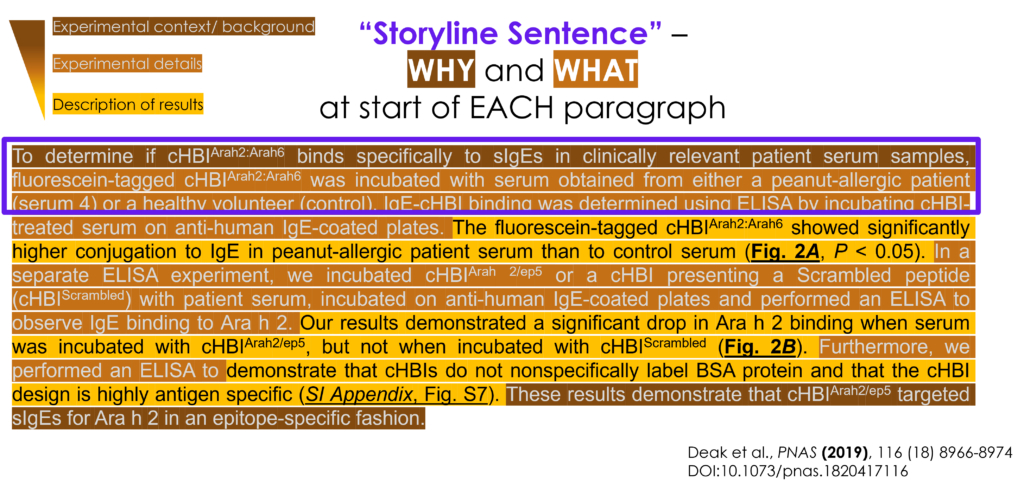

So let’s break down a paragraph from a results section to see how to do this:

This results section is from: Deak et al., PNAS 2019, 116 (18) 8966-8974. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1820417116

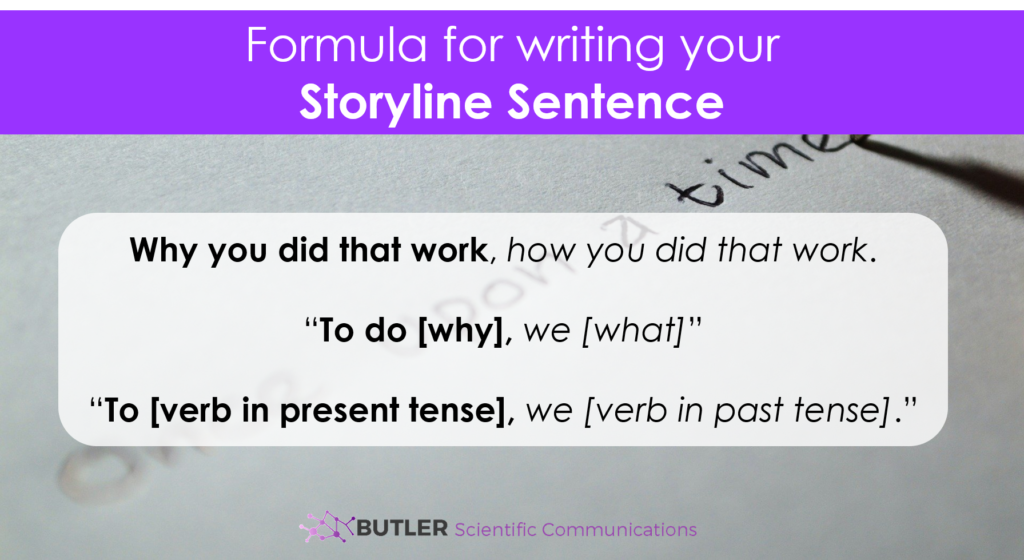

Notice this first sentence, which I call a “STORYLINE SENTENCE” because it walks the reader through the WHAT and WHY of EACH PARAGRAPH of your results to give a good overview of what you did, even if they skim read the paper.

This storyline sentence is setting up the story of your paper.

This sentence starts with the darkest brown color – the context – and moves into the second brown color – some experimental detail.

In this way, this sentence tells the reader WHY you needed to do the experiment you are presenting and WHAT you did to address this question or point.

This makes sure every reader is on the same page as you in terms of WHY you did each experiment.

If a reader cannot understand WHY you did an experiment, they will have a hard time seeing the IMPORTANCE of that experiment!

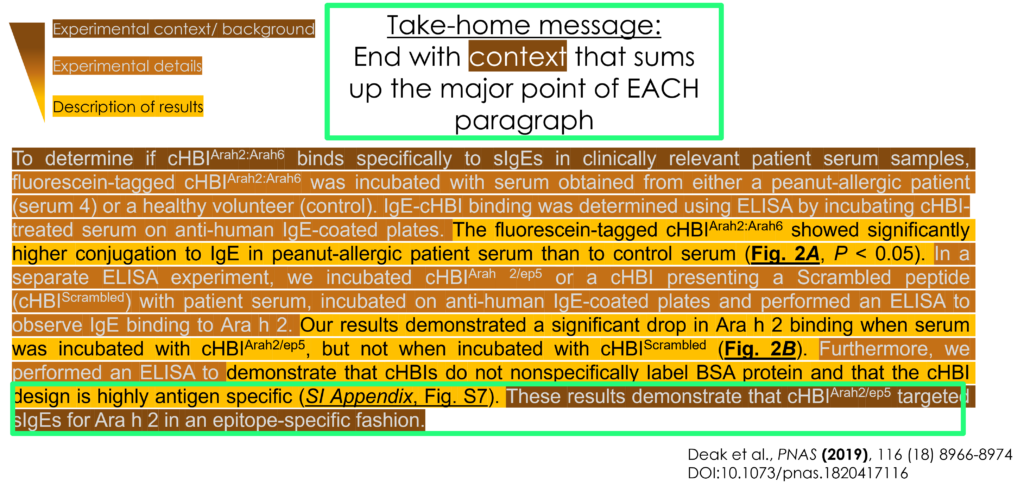

Now, also note that there is also some dark brown context at the bottom of the paragraph:

This TAKE-HOME MESSAGE sentence is often only 1/2 – 1 sentence at the bottom of each paragraph, and it tells the reader the main message they need to know from this paragraph.

We need this take-home message because sometimes a reader can’t interpret your results for themselves.

Maybe its something they haven’t seen before, worked with themselves, etc., but regardless, they might need some help interpreting/analyzing what you saw in the experiment.

Ensuring each paragraph ends with this sentence will ensure your reader knows what they need to know to properly understand your next experiments.

Now there is one last place where we might need to include CONTEXT in our results.

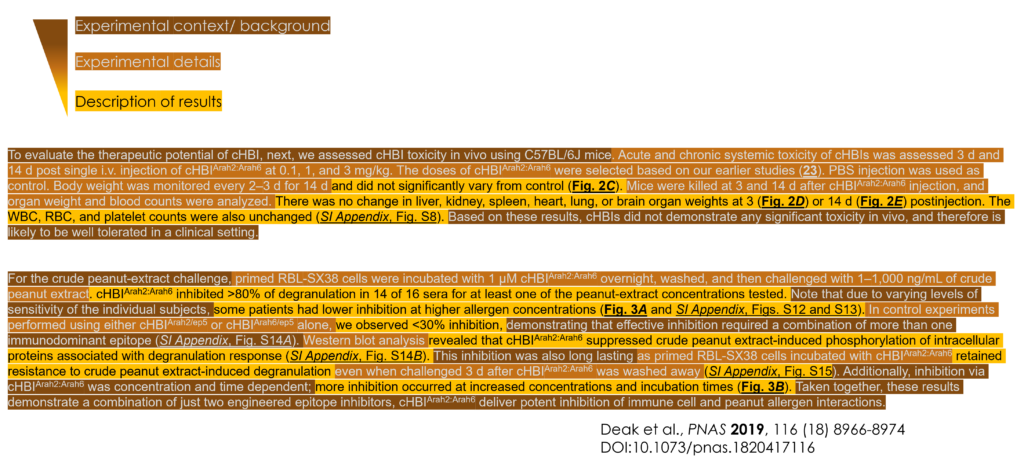

Compare these two paragraphs to see if you can see the difference:

We need to make sure we include enough context in our results paragraphs so the reader can follow along with what we did in our experiments, but this isn’t always required.

Let’s compare these two paragraphs.

The first paragraph here doesn’t have any of the dark brown context WITHIN the paragraph.

This is because the writers of this paper correctly assumed that the readers of this journal would understand the outcome of the experiment without further explanation -> thus, no internal context needed!

Now, let’s contrast this with the second paragraph, which has plenty of dark brown context WITHIN the paragraph.

That is because the writers of this paper correctly realized that the average reader of their journal WOULD NOT understand this experiment or be able to interpret the direct outputs of that experiment without some context and explanation.

Thus, for complex experiments that the AVERAGE READER OF YOUR TARGET JOURNAL might not know how to directly interpret, we MUST include direct statements of context explaining what these results mean or how to interpret these results IN LAY TERMS.

Otherwise, the reader may miss the IMPORTANCE of any experiments they do not understand.

FIX IT: Adding sufficient context in your RESULTS

Add STORYLINE SENTENCES

Luckily, its really easy to add storyline sentences to every paragraph of your results section, though if you want a more in-depth look into WHY we add these, you can check out this post here that is all about STORYLINE SENTENCES!

Otherwise, you can use this exact formula to start every paragraph.

Yes, every one. 😉 I promise no one will notice.

Add TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Just like every paragraph needs to start with a storyline sentence, every paragraph also needs to end with a TAKE-HOME MESSAGE.

To add this:

- include 1/2 – 1 sentence at the end of every paragraph

- use terminology like:

- “…, which means that…”

- “…, meaning…”

- “…, signifying…”

- “…, indicating…”

Add CONTEXT CLUES throughout

Remember to fill in context clues throughout for any experiments that might be tricky for all of your readers to understand.

To do this, follow this list:

1. Determine your audience

2. Estimate the HIGHEST LEVEL COLLEGE COURSE your audience has in common

3. Explain any terms, experiments, or results not standard for that course.

For instance, everyone reading an article in Nature should understand what DNA or RNA are, so you won’t need to explain these, but they might not understand details of more specific technologies that use DNA, like a CRISPR screen.

Add CONTEXT in GRANT PROPOSALS

Grant proposals function exactly as papers here, after replacing “RESULTS” for “PROPOSED RESEARCH”.

Thus, you still need to include in EVERY PARAGRAPH:

- Storyline sentences

- Take-home messages

- Context clues for more challenging experiments

Thus, instead of “we did XXX”, you will write “we will do XXX.”

For more info:

How did it go? How else can we help?

So that is a TON of information about how to fix an unclear importance, diagnose issues in your own work, and how to fix those issues if you find them.

But seeing it written and applying it are two different things.

So, how did this go for you?

Are you still stuck? How?

Comment or ask below – I reply to every one!