The “so what” test can be a powerful tool for making your scientific writing concise and ensuring that it is interesting to your reader.

Effective writing and editing in the sciences requires concise and convincing language, but it also needs to be informative.

There are lots of tips out there for how to do this, ranging from the use of active versus passive verbs or reducing jargon to vague advice like “strive to be concise.”

Common advice also centers around grammar rules, which can be difficult for scientists who haven’t recently taken language refreshers and near impossible for non-native English scientists, and advice doesn’t help if you don’t know how to apply it.

To address this, I started applying and teaching the “so what” test.

To apply this test, just break your paper down into paragraphs, sentences, clauses, or individual words and ask “so what?”

Asking this one simple question and thinking deeply about the answer while editing can remove extraneous words, tighten up vague or rambling sentences, and craft arguments that are more convincing to your reader.

Agreed?

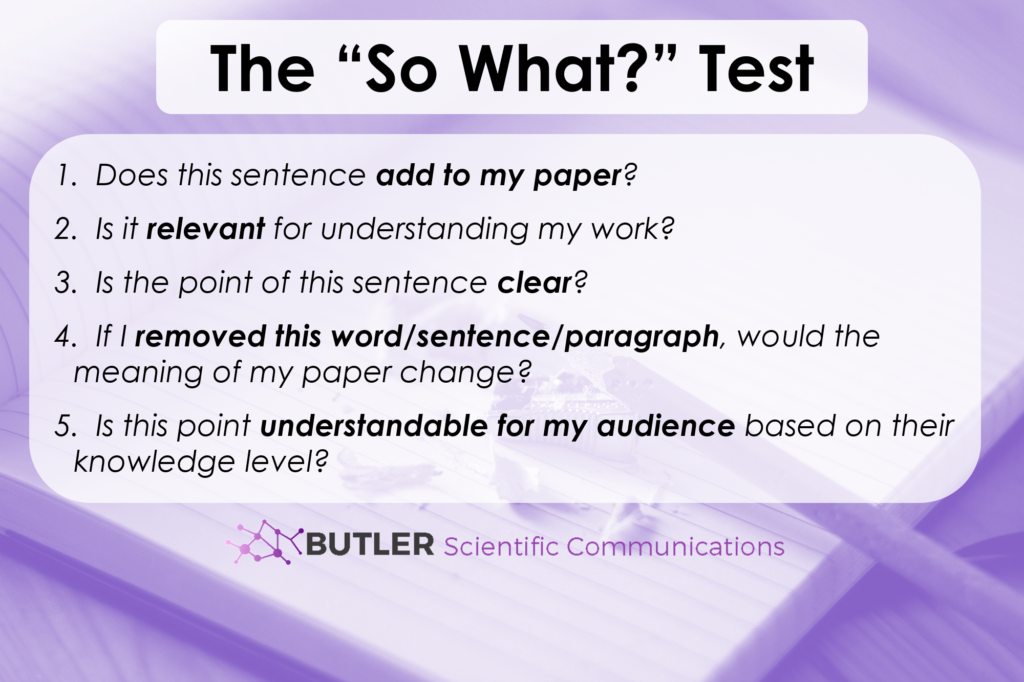

Okay, okay, its not always exactly that easy to really dig into what is going on in your paper, so I have broken my “so what” test down into the 5 most common clarifying questions I find myself asking writers about the content of their work when applying the “so what” test.

Let’s look as some questions to ask yourself during the “so what” test, and then we can expand on these with examples so you can see it in action.

(And don’t forget to read to the end, where you’ll get my BEST technique for cutting 100s or 1000s of words from your manuscript!)

But first, if videos are more your style, we’ve got you covered!

Check out this entire post, including examples and BONUS word cutting technique described in this video:

Questions to ask yourself during the “so what” test:

This question removes vague or unimportant wording from your manuscript.

Does this sentence bring value? Add an important piece of background information? a result? an interpretation of a result?

If not, is it necessary?

This point can also help in structuring your document when used in terms of context – ask yourself if the sentence fits into the manuscript, then section, then paragraph. Maybe this sentence is useful but not in its current location.

These questions remove points that are off-topic and therefore distracting to your overall story.

If the information you are conveying does not advance your specific story or is not needed to understand your science, it should not be included in your paper, no matter how relevant it seems to the field or current audience.

Advance your story, and your story alone, and keep it succinct.

This point addresses writing style.

Can the reader jump right into your sentence and understand what you are trying to say?

If you are unsure, read it out loud or copy it into a translation website to have it read out loud to you. How far into the sentence do you have to listen before you understand the point? Can you bring the point of the sentence closer to the front to better grab the reader’s attention?

Also, try to paraphrase it or have someone else paraphrase it for you.

In doing this exercise, you might see that a sentence is totally irrelevant, that it was already stated in different terms somewhere else in the paper, or that it could be drastically reworded to increase the readability.

This catches repetitiveness and wordiness.

If something can be removed from your manuscript without affecting the meaning, it is irrelevant and you don’t need it.

Use this exercise to remove parts that are stated several times in slightly different ways, remove excess/passive wordiness, and ensure all of your writing is focused and relevant to your story.

i.e., are the terms and concepts either available to the common base level of knowledge available to my readers or have the terms been appropriately explained?

This point can catch unexplained concepts that can confuse your reader.

Make sure that every term in the sentence you are editing is understandable for the knowledge level of your audience.

All manuscripts should be crafted such that a reader would understand this if they took up to the lowest level course common to your journal audience.

For general audience journals, such as PNAS, one must assume that your reader has had the equivalent of chemistry or biology 101. This means that you won’t need to explain to them what RNA is, but should include a brief clause defining the function of microRNA or siRNA.

Example: So how do we apply this “so what” test to our own work?

“Polymers have been recently applied to enhance therapeutics.”

“So what?”

Even if your paper is about applying polymers to therapeutics, does this sentence add something to your paper or your argument?

Not really, because there are no real facts in this sentence, meaning it doesn’t add value, and because the reader is already reading a paper on a polymer that was applied to therapeutics (hopefully this is what this paper is about, or this sentence is REALLY extraneous!), they likely already know this information.

If you removed this sentence from a paper on polymers and therapeutics, would the meaning be changed? Likely not.

Looking at some of the individual words here also brings up some issues. What types of polymers? therapeutics? What is meant by “recently”? This month? this year? this decade? How about “applied”? Are these polymers conjugated to therapeutics? Used as nanoparticle carriers?

Overall, sentences like these are common in science, and everyone writes them. They are the first-draft idea sentences that are helpful for “outlining” the overall structure of the paper (its easy to fill in a paragraph after this sentence about the important background of polymers in therapeutics), but they all too often make it to final drafts and bog down the overall text.

Therefore, how do we use the “so what” test on this draft sentence to increase the impact of our writing?

First, we can make it more specific for our paper.

What types of polymers are we writing about? How have these specific ones been applied to therapeutics? What do our applied polymers do to enhance therapeutics? Is there a specific mechanism or enhancement that we are focusing on? What is the history behind that and/or what are some existing examples of these polymers or applications?

Second, if this information is in a later and sentence and this was just a lead-up sentence, do we need it?

Likely, we can delete it, and our paragraph will have the exact same impact. Otherwise, this information can be integrated into a future sentence(s) to keep the flow moving in a way that is more useful to our reader.

Last, how can change our vague words to provide more specifics that can make the writing more interesting for our reader?

As an example, we could write something like:

“In the past 10 years, PEG-based polymers conjugated to fast-clearing therapeutics have been demonstrated to increase the circulation half-life.”

This sentence answers many of the questions that came up in our “so what” test. First of all, we have used adjectives to describe our vague nouns that make the sentence (and therefore the manuscript) much more specific.

This can actually improve our readership, and therefore our impact, by appealing very strongly to a small class of readers, which is better than not really appealing at all to a broad class of reader.

Next, we made this sentence mean something. Now the reader will learn exactly what types of polymers do a very specific thing in the field of therapeutics.

This will also focus the readers attention to key points we want to highlight (PEG polymers and increasing the half life of therapeutics) instead of a sentence that will cause their mind to drift away.

Obviously this sentence could be changed in a variety of ways depending on what the paper will highlight, though its a great start for making a clearer, higher impact sentence.

Lets look at another example:

“The polymer developed herein showed a better half life and less toxicity to match the desired therapeutic requirements.”

While this sentence does highlight the results of this study, it is again almost too vague to be of use.

Why?

The reader doesn’t know what “better” means, and likely will be flipping back through the paper to see the result from the polymer as well as the therapeutic requirements.

In fact, words like “better/worse”, “higher/lower”, etc. should never be used without a qualifying number and something to compare it to. It MUST always state 4-fold better, 3x higher, etc., and as compared to WHAT.

This also applies to significance…never state that a results is significant or non significant without listing the p value in the sentence.

Additionally, if there was more than one polymer tested in this study, it should be specified, and the therapeutic requirements should be restated.

In terms of providing more meaning to the reader, the writer of this sentence should also consider adding a “so what” clause or second sentence. These clauses often start with “, meaning/demonstrating/showing/indicating that…” and explicitly state why this is important or matters.

So how could this sentence be changed to pass the “so what” test?

“Polymer-drug conjugate MC121 therefore showed a twenty-fold longer half life than the drug alone (~20 h vs 1 h) with no demonstrated toxicity in mice. This means that it can be a good lead target for the treatment of target disease, which requires a half life of greater than 5 hours to avoid constant infusions.”

But adding all of these extra words makes my manuscript so long, and I am already over the word limit!

Yes, sometimes being more specific can make a sentence longer than the vaguer version of the sentence, but the “so what” test can also be used to shorten a manuscript.

For example, I bet you’ve seen a lot of this type of scientific writing:

“The polymer was applied to the extension of the half life of this drug in order to reach a half life of over 5 hours to avoid the need for constant infusions of the drug.”

By applying the “so what” to this sentence, we find that close to half of the wording in this is superfluous and the sentence is still vague.

Phrases like “was applied to” make for convoluted sentences that do not provide much information. Why do we need to say something “was applied to the extension of…” when “extend” will do that in one word, or when “was applied to” could be made much more specific, such as “was conjugated to the free carboxylic acid of…”.

Also, the excess wordiness and the passive structuring of the sentence makes it difficult for the reader to understand, as the point of the sentence appears roughly halfway through and is a bit buried in wordiness.

If a reader isn’t paying close attention, it is possible they will lose track of what this sentence is trying to say before it gets to the point.

Therefore, the “so what” test is telling us that we should remove excess wordiness and make the point of this sentence stand out better, while adding specifics where possible.

What if we tried:

“To extend the drug half life to greater than 5 hours to avoid constant infusions, we conjugated polymer 121 to the free carboxylic acid of MC.”

Or, to make a completely different and yet still more readable sentence:

“We hypothesized that conjugating various polymers (1, 2, or 5 kDa) to MC could provide a conjugate with a half life of greater than 5 hours to avoid the need for constant infusions.”

This application of the “so what” test is great for shortening and tightening up sentences, but when the entire document is too long, sometimes more drastic measures are needed.

In these cases, compose your next draft using an “additive so what” test.

For this version, start with a blank document, copying in one sentence at a time. To each sentence that is copied into your new draft, apply the so what test again, but only copy in those sentences that pass.

In this situation, instead of asking “what is unimportant enough to remove?”, ask “what is important enough to keep?”

The mindset shift here seems subtle, but it makes a huge impact on tightening up writing.

Each sentence therefore needs to prove its worth to make it to the final cut, which is more difficult/strict than a sentence needing to be not exactly superfluous.

Over time, the “so what” test becomes ingrained into your writing and doesn’t need to always be an extra step.

It will eventually be easier to spot the vague or unimportant phrases while writing and correct them on the spot.

Oh hey – that sounds like just like becoming a better scientific writer!

If you still want a bit more help, though – you can always check out our workshops on writing scientific manuscripts!

Happy writing!

PS. We’d love to see your best examples of sentences that didn’t pass your “so what” test and what you did to fix them!

Post your examples in the comments…