Why the scientific paper structure? It mimics the research process!

Science can be daunting enough – the scientific paper structure doesn’t have to be, too!

In fact, the structure of a scientific paper is meant to be anything but daunting, as it is designed to mimic how science actually progresses.

Don’t believe me? Think about this –

–>Research usually starts with a topic (title).

–>Then, you need to study the state of the field around that topic, identify key gaps to address, and form a hypotheses (introduction).

–>Next, you gather the tools and equipment you need to do that research (materials) and perform experiments (methods).

–>After that, you report the results of those experiments (results) and see how those results affect the field and integrate back into it (discussion).

Helpfully, that is also exactly how your scientific paper is structured.

A scientific research paper is typically ordered:

*Note: This page is going to walk you though the scientific paper structure. If you want info on writing each of these sections, please see my comprehensive page on writing your scientific manuscript!

Scientific paper structure: IMRAD and scope

In more technical terms, the scientific paper is usually structured in what we call the IMRAD format, standing for “Introduction, Methods, Results And Discussion.”

An IMRAD-based paper includes:

- Why did you do this research?

- What was the original hypothesis?

- When, where, and how did you do this research?

- What materials or subjects were involved?

- What did you discover?

- Was the tested hypothesis true?

and

Discussion

- What do your results mean?

- How does this fit within the field?

- What are the future prospectives?

Besides mimicking the research process, the structure of an IMRAD paper is also helpful for the reader in terms of the the scope of the paper and is designed to draw them in and then show them how your work matters.

What is the scope?

The scope indicates how broadly or narrowly the writing is focused. If the writing in a certain section has a broad scope, it is designed to be accessible to a broad audience. If the writing in a section has a narrow scope, it is designed to be the most focused on your specific work – which is directly accessible to a much smaller audience.

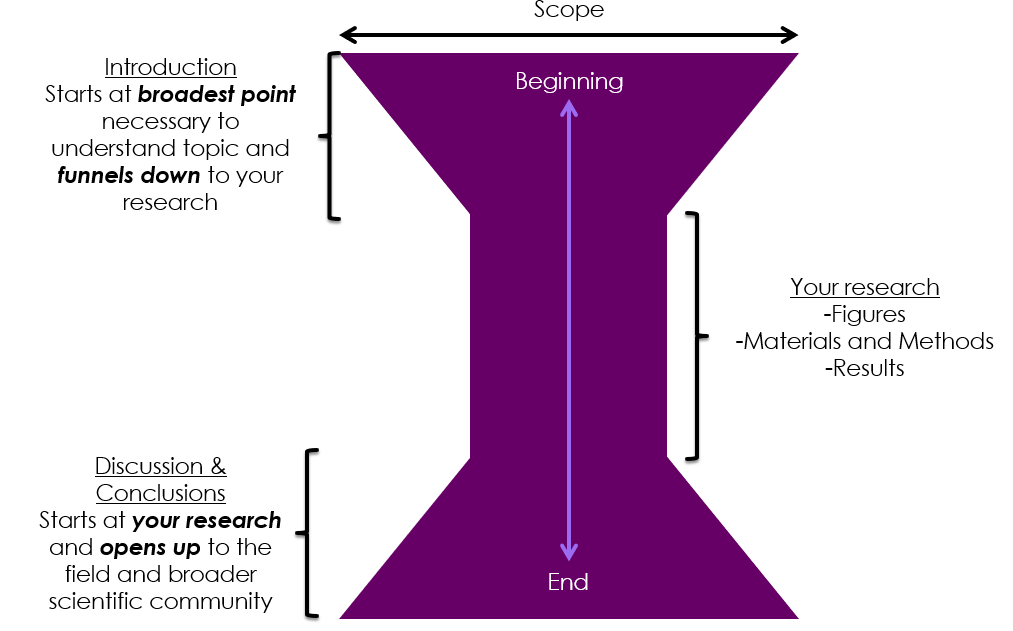

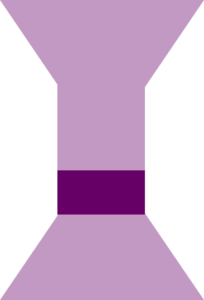

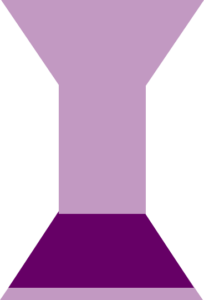

To show you what I mean, I made this diagram that shows how the scope of an IMRAD paper changes from beginning to end:

Note how the scope of a scientific paper makes an hourglass shape.

This makes sense, as the important results of your paper are the narrowest in scope. Because this scope is so narrow, it is not widely known, so it would not be accessible to a reader unless it was bookended with information that is much broader in scope, or information that is more well known and understood. This is how you teach the reader what they need to know to understand your work and give them the tools to place your work in context.

Therefore, the introduction of our paper is going to start at the very broadest scope, first introducing the reader to our field in general and then to our research more specifically. In this way, we will start at a very broad scope and slowly narrow into the results – which represent the narrowest scope in our paper.

Scientific paper structure: Key parts

1. Title and Abstract: Attract the reader’s attention

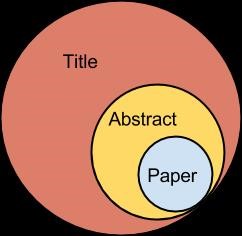

A scientific paper usually starts with two key parts that help attract a reader’s attention to your work: the title and abstract.

These parts are designed to essentially be the advertisement for your paper.

This means they need to be informative enough about the content of the paper to attract the right readers to your paper, and they also need to be written in a way that is interesting enough to attract those who might not otherwise find your paper.

Also note, basically any reader who gets to the paper body will have read your title and then abstract. By making sure your title and abstract are as attractive as possible, you can get more readers interested in also reading the paper body!

Title

The title contains the key words of the paper, and tries to organize them in a way that lets the reader know what kind of study you conducted and roughly what you accomplished in that paper.

For all of my advice on writing your title, go here.

Abstract

The abstract is also written to draw attention to your papers, so you want to structure it in a similar hourglass shape as the paper body.

The abstract should

- start with a broad problem that is relatable to the average reader of that journal

- indicate how your proposed to solve that problem (hypothesis or research objectives)

- give a few lines about what you did in the paper, including key methods and results

- end with a statement about why your work is important and why it deserves to be published.

This is a lot to ask of a normally 250 word abstract!

Don’t worry – I show you exactly how to do this. For all of my advice on writing your abstract, go here.

Or, you can download your free abstract writing guide here.

2. Introduction: Introduce the reader to your work

After the reader has opened your paper, they need to be introduced to not only your work, but why it matters. This is where the introduction comes in!

Most scientists are good at introducing the literature surrounding their field – which is a big part of the introduction – but struggle to convey the importance or necessity of their work.

Part of this is because many people fail to see the importance of introducing the entire field to the reader to show why it is important to do research in that field.

Therefore, the introduction should start with a very wide overview and include a paragraph at the beginning that introduces the entire field to the reader.

Paragraphs of your introduction

Paragraph 1. The first paragraph of the introduction should answer the question – “Why does my research field exist?”

Importantly – this paragraph should include a very clear statement of a gap that still exists in the world that your field of research seeks to fill.

Paragraphs 2-3. Next, it is important to introduce to the reader why your research project exists, which involves the traditional review of relevant literature that most scientists are comfortable writing. These next 1-2 paragraphs should answer the question – “Why does the research in this paper exist?”

Importantly – these paragraphs should include a very clear statement of a gap that still exists in the field that your specific research project seeks to fill.

Paragraph 4. The last paragraph of the introduction should give the reader an overview of what to expect in this paper. It should include a typical “Here, we did…” sentence as well as a very short summary of key methods or results.

But we aren’t done yet…

This final paragraph should also end on a sentence that answers the question – “Why does this work matter and deserve to be published?”

The most impactful introductions all end with this forward-thinking statement that helps the reader place the product of your work into context. Don’t underestimate this sentence – getting the “why” into your reader’s head from the beginning can do wonders for their ability to grasp the importance of your work.

For all of my advice on how to write your introduction, go here!

3. Materials and Methods: Tell the reader what you did and how you did it

After setting up why your research projected needed to exist and what you hoped to accomplish, it is time to tell the reader what you did and how you did it.

In terms of text, this section on your materials and methods is the narrowest in scope of all of you paper, as it related to your project alone.

In this section, you need provide enough detail that your work could be repeated.

Tell your reader:

- what materials you used and where you bought them

- what equipment you used

- what protocols you followed

- how you did each experiment

- how you analyzed your results

- how you calculated statistics

If you want your work to be considered robust, others need to be able to repeat it.

At this point, your paper should convey what another lab would need to know to copy what you did in this work.

4. Results: Show the reader what you saw

The final section of the narrow scope in your paper is your results, where you tell the reader what you saw in your experiments.

These paragraphs tell the story of your paper, and should be designed as such.

For the best readability of this section, the results should be structured such that each paragraph:

- represents one experiment or group of related experiments

- begins with a topic sentence that tells the reader what you did in that paragraph and why

- end with a summary statement (1/2 – 1 sentence) telling the reader the main take-home point of that paragraph

The results section should not:

- contain large amounts of introductory explanation with references – save that for the introduction!

- Provide extra introductory info only when it is needed to understand the following work and does not apply to the entire paper

- contain large chunks of experimental detail – save that for the methods!

- Provide only enough here such that the reader understands what experiments were done and what the controls were.

- The reader should not be able to reproduce your experiments from the details in this section

- contain detailed analyses of the results – save that for the discussion!

- Provide only enough for the reader to understand the rest of the paper plus the paragraph-ending summary statement.

For all of my advice on how to write your results, go here!

5. Discussion: Walk the reader through what your results mean and how they affect the field

At the end of the paper, the reader needs to know what your results mean and how they integrate in the field – it is the only way to understand the importance and impact of your work!

For this, the discussion is the opposite of the introduction – it funnels the reader OUT of your work, building on your results to connect your work to the field and society as a whole.

Paragraphs of your discussion

Paragraph 1.The first paragraph briefly summarizes the main results of the paper and directly shows how they address the gap in the field that was mentioned in the introduction.

Paragraphs 2-4. These middle paragraphs discuss your results. For each paragraph, take one key result and:

- analyze it – what does it mean?

- relate it to the field – how does it tie into other work in the field?

- relate it to the gap – how does it help fill the gap that you discussed in the introduction?

- speculate beyond the current limits of the field – what new research questions do these results bring up?

- future directions – how can this research be expanded on in the future?

Final paragraph – the conclusion. The conclusion should never be a summary of the paper – this misses a great opportunity to highlight the importance and impact of your work, and leave the reader with a forward-thinking outlook.

The conclusion does a disservice to your paper if it doesn’t highlight why your work deserves to be published. Make sure it answers:

- Why should scientists be excited about this work?

- Why should non-scientists be excited?

For all of my advice on how to write your discussion, go here!

Scientific paper structure: Putting it all together and writing

Now after seeing how a scientific paper is structured and why, you might still be struggling to write the paper…don’t worry, this is completely normal!

Just because we know the structure we need to strive for, it still isn’t easy to translate our work into a paper. This is because the way a paper is structured is designed to help the reader through the process, but it is not necessarily the easiest ordering for writing a paper.

To now learn how to WRITE your scientific paper, you can find all of my advice on that topic here.