I’ve had an especially high number of papers from newer, less experienced authors recently – pandemic-induced paper writing! My post today is inspired by one comment that I’ve been making to these authors over and over – missing the opportunity to make a compelling story by forgetting what I call storyline sentences.

Storyline sentences, forming the first sentence of each results section, I have so named for how they define the story of the paper and help draw the reader in.

In other words, I want every paper I edit to have a sentence at the start of each paragraph that tells a coherent story the reader can follow.

By following this structure and making absolutely sure you have set up a story that the reader can follow, you make it such that the reader doesn’t have to dig into your work to figure out what your story is.

I want the burden of understanding the point of a paper placed squarely on the shoulders of the writer, and not on the reader who has a million papers to get through.

Why this one quick change can instantly make you a more experienced writer

Because this is overwhelmingly an issue I see with newer authors, it seems like as writing experience improves, academics tend to pick up on the need for this sentence and start to automatically include it in their writing.

But the cool thing here is that with this one simple change of adding a storyline sentence to papers, a newer author can appear much more experienced!

So today I’m going to run through why these sentences are so important for crafting the story behind your paper and making that story apparent to your reader.

Why is writing a compelling story so important?

As a young scientist, I used to get so frustrated with what I considered to be the hoops I had to jump through to get people to understand my work.

Wasn’t good science supposed to stand for itself? Shouldn’t the importance and impact of your work shine through no matter what if it is good enough?

Well, unfortunately, the answer to that is mostly no.

Why only mostly? For the experts in your field – the people doing almost exactly what you are doing – then yes, the importance and impact and overall logic behind what you did will show through if you focus your writing on letting the science speak for itself.

However, those same experts will likely read your paper anyways, as its is normal to read the papers very closely associated to your own work. We don’t want to write for those people who are going to read our work anyways – they are going to read and understand our work anyways.

To spread the word about our science and reach the greatest number of people, we want to write for the ones who might not necessarily open our paper otherwise.

So, if we want to pick up those people that might not be so interested in our work, we need to do it with a compelling narrative that hooks the reader and makes them want to keep reading.

You get no second chances to attract a reader

Think about how you read journal papers, especially those ones you don’t HAVE to read.

First, that paper needs to attract your attention with an interesting title and abstract – we will get to those in other posts.

But then once you decide to open that paper – how do you read it? Do you ever pick up a new paper and read it from start to finish?

I know I most certainly do not.

First, I will have 83 tabs of papers I want to read open on my browser. When I do finally get time to read papers, I certainly don’t have the time to open each one and read it from beginning to end.

In fact, most people don’t, and instead skim papers to see if they attract their attention and if they are interested in the story.

Most readers are like me – with too many tabs to sort through. If a story loses my attention or is hard to follow, I definitely don’t spend the time to figure it out and dig into what the writer was trying to say.

That means if a story loses my attention – I stop.

I close the tab.

There are no second chances in catching and keeping your reader’s attention.

So this means we need to put as much information as possible where the reader will look for it and make it as easily digestible as possible to keep their interest and keep them from closing that tab.

How readers skim online articles

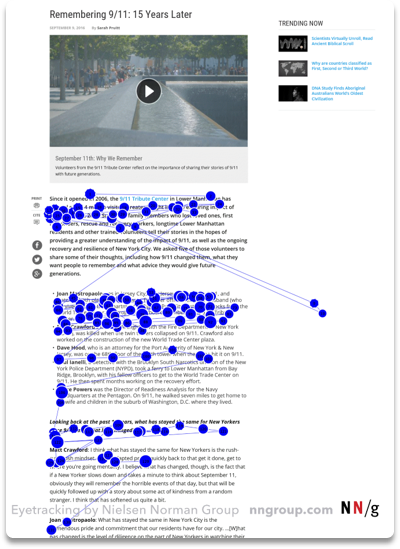

What is cool about this is people have studied exactly how readers usually skim online articles, and we can use that to our advantage when writing. If we know where readers are going to look, we can put the information we definitely want them to read in exactly those places.

What these studies have found is that readers usually read blocks of text (meaning a formatting like you will have in your online paper) in an F-shape.

This image from the Nielson Norman Group site (https://www.nngroup.com/articles/f-shaped-pattern-reading-web-content/) shows the F-shape in action, with the blue dots showing where the reader’s gaze rested.

What you can see here is that the reader mainly reads the first sentence of each paragraph and moves on to the next.

Which is bad news for your article if you get to the point of a paragraph later in that paragraph.

The point here – for a compelling story, put the point FIRST. That way, if the reader skims, they at least get the point and can follow your story.

Example of a compelling story that holds attention – look at the storyline sentences!

To really highlight the importance of these storyline sentences, let’s check out the story told by this article by Galvez and Bode, published in JACS in 2019 (https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b03597). It is a great example of using storyline sentences, as you don’t need any more than this first sentence to get the point of the paper.

To show you what I mean, I took the first sentence of each paragraph of the results and have pasted them here.

Read these sentences, paying attention to the structure of the beginning of each. It ensures the reader knows exactly what is going to happen in that paragraph:

- As our molecular template of choice, we selected the streptavidin–desthiobiotin pair by linking the ligating functional groups to desthiobiotin.

- While using a weakly associating ligand may allow it to dissociate from unproductive arrangements, such a system would unnecessarily complicate the analysis of the ligation and kinetics. We therefore elected to use desthiobiotin and adopted two approaches to minimize nonproductive binding arrangements during our validation of a true traceless templated ligation.

- To accurately monitor the rate of ligation, we designed starting materials whose conversion could be determined at low concentrations by real-time fluorescence measurements (Figure 2b).

- With the starting materials in hand, we screened a number of streptavidin mutants and reaction conditions.

- To further confirm our hypothesis that streptavidin assists the amide formation by binding both 1aand 2a, we formed a 1:1 complex (1a–S) of 1,2-divalent streptavidin and 1aand isolated it by FPLC.

- To provide a mathematical model for the effect of templation on the rate of product formation, we adopted pseudo-first-order conditions ([2] ≥ 10·[1]).

- To further evaluate the validity of our model, we conducted kinetics experiments under pseudo-first-order conditions (Figure 4).

In reading through these sentences, you can automatically figure out the story of their entire paper – by just reading one sentence!

Pretty cool, huh?

Key point of storyline sentences – state your WHY

So how did they do it? Notice the parts of the sentence that I underlined – they all start with a WHY…

Each sentence of their results starts with WHY the authors were going to do the work found in that paragraph.

The authors have made it impossible to miss why they did the work in each paragraph of this paper by making it the absolute first thing the reader reads in each paragraph.

This is an especially crucial point, because there is an assumption I see often in science writing that readers should be given only concrete facts and left to make up their own minds.

This means that the “whys” are often ignored and the reader is left to infer these. The why is sometimes seen as too subjective for science writing and is left out.

This is a shame, though, and the opposite of what we really want.

To tell a good story, we need to draw readers in with a story of why we did the work in the way that we did.

This means we need to include our why.

In fact, telling the reader the “why” is exactly how you help craft a good story through the body of your paper.

How to write a storyline sentence – make your story compelling!

Like I mentioned a the beginning of the article, the good news here is that this is an easy fix.

Look back at those storyline sentences I copied from the JACS paper – they all have the exact same format.

This means that writing a good storyline sentence can be broken down into exactly a formula that you can apply to your own work!

So what is that formula? We’ve already shown that each sentence first includes the “why this work was done“, as highlighted below…

- As our molecular template of choice, we selected the streptavidin–desthiobiotin pair by linking the ligating functional groups to desthiobiotin.

- While using a weakly associating ligand may allow it to dissociate from unproductive arrangements, such a system would unnecessarily complicate the analysis of the ligation and kinetics. We therefore elected to use desthiobiotin and adopted two approaches to minimize nonproductive binding arrangements during our validation of a true traceless templated ligation.

- To accurately monitor the rate of ligation, we designed starting materials whose conversion could be determined at low concentrations by real-time fluorescence measurements (Figure 2b).

- With the starting materials in hand, we screened a number of streptavidin mutants and reaction conditions.

- To further confirm our hypothesis that streptavidin assists the amide formation by binding both 1aand 2a, we formed a 1:1 complex (1a–S) of 1,2-divalent streptavidin and 1aand isolated it by FPLC.

- To provide a mathematical model for the effect of templation on the rate of product formation, we adopted pseudo-first-order conditions ([2] ≥ 10·[1]).

- To further evaluate the validity of our model, we conducted kinetics experiments under pseudo-first-order conditions (Figure 4).

And then the second part of the sentence – can you see the pattern? I have highlighted the first part to help 😉

- As our molecular template of choice, we selected the streptavidin–desthiobiotin pair by linking the ligating functional groups to desthiobiotin.

- While using a weakly associating ligand may allow it to dissociate from unproductive arrangements, such a system would unnecessarily complicate the analysis of the ligation and kinetics. We therefore elected to use desthiobiotin and adopted two approaches to minimize nonproductive binding arrangements during our validation of a true traceless templated ligation.

- To accurately monitor the rate of ligation, we designed starting materials whose conversion could be determined at low concentrations by real-time fluorescence measurements (Figure 2b).

- With the starting materials in hand, we screened a number of streptavidin mutants and reaction conditions.

- To further confirm our hypothesis that streptavidin assists the amide formation by binding both 1aand 2a, we formed a 1:1 complex (1a–S) of 1,2-divalent streptavidin and 1aand isolated it by FPLC.

- To provide a mathematical model for the effect of templation on the rate of product formation, we adopted pseudo-first-order conditions ([2] ≥ 10·[1]).

- To further evaluate the validity of our model, we conducted kinetics experiments under pseudo-first-order conditions (Figure 4).

So hopefully you can see that the second of the sentence is simply an action on your part. They are all a 1st person account of the work that you did to address the why you mention at the beginning of the sentence.

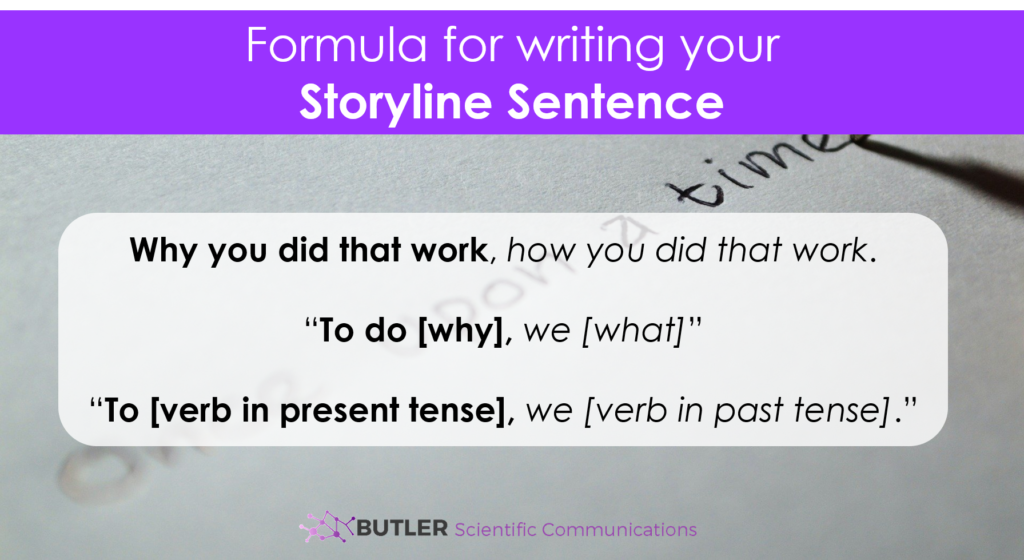

Formula for writing Storyline Sentence – tell a compelling story!

Because every sentence here follows the same pattern, it is easy then to break that pattern down into a formula that you can apply to the first sentence of all of your results paragraphs to tell a compelling story.

Overall, each one of these sentences contains:

- a WHY – why did you do this work?

- a WHAT – what did you do to address the WHY?

So your storyline sentence for each paragraph looks like:

To do [WHY], we did [WHAT].

That’s really it, and it is that simple.

Start every single paragraph of your results section with a sentence that follows that formula, and you will tell a much clearer story, engage a reader, and elevate the level of your manuscript.

Does it matter that each paragraph starts the same? Isn’t that repetitive?

Nope – not a bit! Each one of these sentences is separated by an entire paragraph of text – it doesn’t sound nearly as repetitive as you would think.

Also, the point of this is to make it as easy for your reader to read as possible.

Starting each sentence the same and putting that key information right up front makes it so easy to read that the repetitiveness of it is only secondary to the ease of finding the information.

So there you have it, how to elevate your writing and tell a compelling story in one simple step.

Are you already doing this in some of your paragraphs?

Can you apply it to immediately to make sure you tell a compelling story in your paper?

For more on including enough context in your results, go here!