Hello all, and happy February!

It seems like everyone is using 2020 to dig in and get some papers going, which is great to hear! In all that paper bustle, though, I’ve had several requests for some posts on introductions. Mainly:

-how to keep it interesting

-how to keep it focused and concise

-how on earth you figure out what to write in an intro

Because this is a lot to tackle in one post, we’re going to start with the basics you need to get your introduction written.

For now, this includes:

-Relating your work to the gap in the field

-Structuring your introduction like a funnel

-The four main paragraphs of your introduction

The key component of your introduction – THE GAP

There is one key point that you want to make sure you get across in the introduction of the paper – the gap in the field that your work sought to address.

What is this gap? To help you figure out what yours is, this can be:

- a problem that still exists

- a new problem that has arisen through recent research

- a drawback to an existing method

- a question that has not been answered

- an unexplored parameter of previous research

- a hole in general knowledge

- the reason you did this work

Essentially, this gap tells the reader where you work fits into the grand scheme of things and your reason for addressing this gap explains why your work is important and why it matters.

This means making it very clear what hole you tried to fill, question you sought to answer, data you tried to discover, etc. with your work, which tells the reader (or editors and reviewers!) why this work matters and deserves to be published and put out there in the world of science.

If your reader leaves your introduction with nothing else, they should know this gap you tried to fill and how you went about doing that.

The gap is also such an important thing to highlight in the introduction, most of the writing in the intro should relate back to this gap. I will indicate how to do that for each paragraph below.

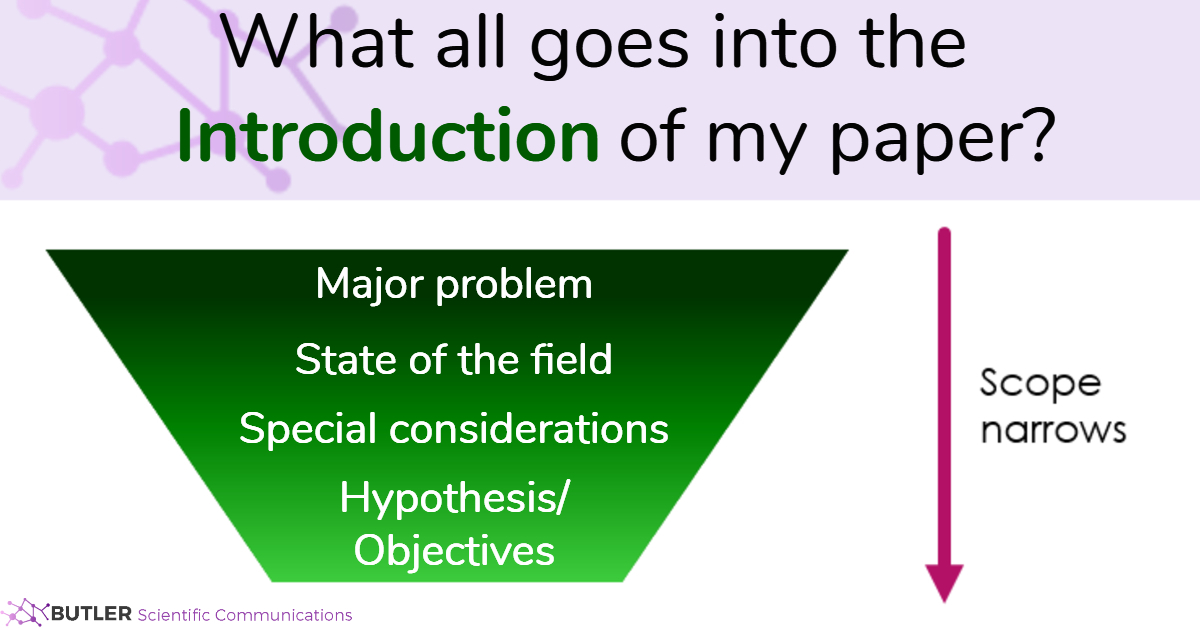

Your introduction is a funnel

The purpose of an introduction is to capture a reader’s attention and then teach them what they need to know to understand the work that you did.

The best way to do this, therefore, is to structure your introduction like a funnel – with the broadest scope at the top to capture attention and then a narrowing scope as you bring the reader in and teach them about previous work in the field and what you did.

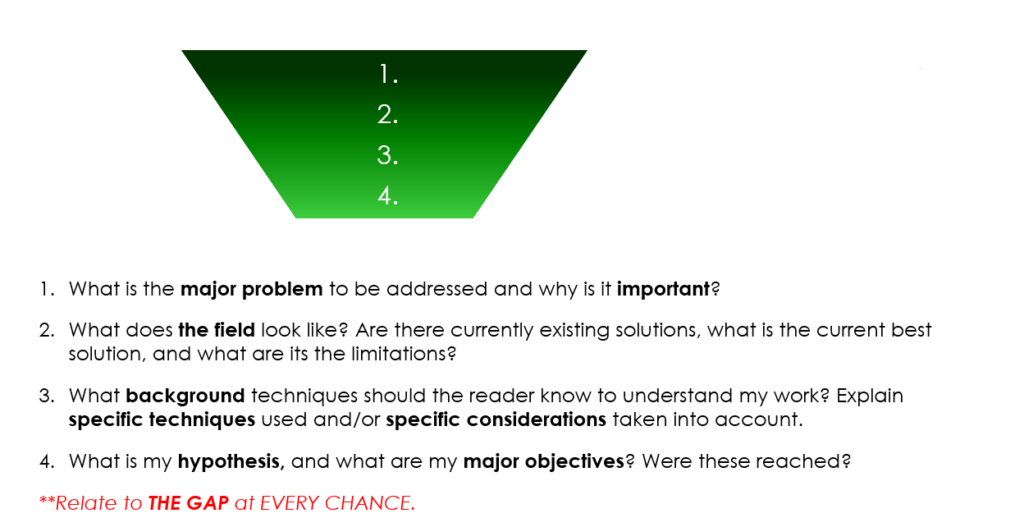

Four main sections of an introduction

Now we’ll show how we can break that funnel up into four main sections to further simplify your writing.

As a general rule of thumb, limiting each of these four sections to only one paragraph keeps the introduction concise and to the point.

There is one exception – Section 2 may consist of more than one paragraph only when more space is needed to describe the field as relates directly to the gap (more in section 2 below). As in, you need to explain so many concepts in the field, which are all necessary for the reader to understand you work, that it cannot be easily confined to one paragraph. This is common in fields like biology, where complex pathways might need to be described for the importance of your work to be obvious. Otherwise, more than one paragraph in section 2 is considered a literature review and should be condensed into only that which is directly relevant to the gap you are addressing.

As you have probably now suspected, each of these paragraphs should have a reference to that all-important gap in the field.

1. The major problem and why it is important

This is the part of the introduction that should have the widest scope.

This is because the first thing that an introduction must do is introduce the reader to the problem that you sought to address in your paper and tell the reader exactly why that problem matters. This means that this first paragraph is often more related to what will interest a reader than your specific research.

As an example, you might open your introduction by explaining why diagnosing cancer is a major and important issue, even if your work is not so applied as to ever been directly used to diagnose cancer.

That is because readers will be more interested in the broader topic than your overall narrow one, and it helps show the importance of your paper when you show an overall problem that your work could potentially address….even if that problem is bigger and broader than the scope of your research.

The entire point of this paragraph is to attract the attention of a reader and show them the importance of the problem you are addressing.

If you, the expert in the field, do not tell the reader why it is important to address the problem you are discussing, they likely will not have the background in your topic to figure it out for themselves. It is therefore very important to make this clear early on in the paper – this is what will help attract a broader readership to your paper than the experts in your field who would likely read your paper no matter what.

We’re asking a lot from our first paragraph, because the next thing it must do it convince the reader that they, too, should care about this major problem. Without giving a reader a reason to care, they likely will not, because again, they likely will not see this for themselves. Convincing the reader to care about this overall problem, though, is the single best way to get them interested in your paper.

Finally, this already packed paragraph needs to convey to the reader the what step forward you are taking towards this overall problem that the reader now cares about. In broad terms for this first paragraph (remember your broad scope here!), how did you try to address this problem? Using our cancer example above, instead of delving into the nitty gritty details, you might say “Therefore, we sought to develop a diagnostic tool with a better sensitivity to detect this cancer before it becomes too late to treat.”

2. The field

We narrow our scope slightly now in the second paragraph – bringing the now-interested reader into the field to show them what has been done to address this problem in the past.

Therefore, this is a mini description of the literature, though only as it relates directly to your specific gap. It is NOT a comprehensive literature review and should not strive to be one.

This paragraph should indicate what has been attempted so far towards this gap you are addressing and why these previous attempts have fallen short, constantly highlighting what gaps still exist in achieving this goal.

Essentially, the reader should finish this paragraph with a clear sense of what has been tried before you (still directly related to your specific gap), the current drawbacks of the previously attempted work, and what gap still exists and why.

The paragraph should provide a sense of what your competitors are doing, but why your work still matters in light of that.

This is the one section of the introduction that might include more than one paragraph, though care must be taken that it does not devolve into a full literature review. In certain fields or for specific projects, there will be a considerable amount of literature that needs to be discussed for the overall work to be properly evaluated. This work must, however, always be able to be related directly to the gap in the field for its inclusion in the introduction. Otherwise, it should be considered a partial literature review and irrelevant for your manuscript – at which point, it should be deleted.*

In other words, a good rule of thumb here – if you can write a short clause explaining why each piece of literature you are including directly addresses your gap in some way, it can be included here. If not, it is extraneous information.

*Caveat – this is for scientific manuscripts following an IMRAD structure. Certain fields of research DO include a type of literature review in a manuscript (engineering and math, for example), and I am not talking about that type of extended introduction here. These manuscripts will still have an “opening” to their literature review that follows these introduction guidelines, and my rules here will apply only to that initial section.

3. Background and special considerations

This third paragraph delves even deeper into the details of the how you are going to accomplish this goal, narrowing the scope even further. It provides the reader with the specific details they will need to understand your approach towards solving this problem. It should cover any specific techniques that are used in your work and explain why these techniques were chosen over others. It should also highlight any specific considerations that went into a project, such as properties that a molecule needed to possess or key points a new methodology needed to have.

This is the paragraph that is often similar between lab papers, as it contains lab-specific techniques and technologies that are applied to solving specific problems.

If you need to include a list of considerations that needed to be accounted for in your project, or explain a very specialized technique you will be using, this is the paragraph for that.

This is the one paragraph of an introduction that can be skipped, as not all projects will have these specific considerations that will need to be explained to a reader.

Finally, as with every paragraph, you should again relate this to the gap in the field. If you needed to use a specific technique, explain why its important for addressing the gap. If you needed special considerations, explain why.

4. Hypothesis and major objectives

The final paragraph of the introduction tells the reader your hypothesis and lays out the specific major objectives you sought to address in the paper. This is the section that narrows the scope sufficiently to bring the reader into the very narrow scope of the results of the paper, acting as a bridge between the introduction and your results.

Essentially, the reader needs to finish this paragraph knowing exactly what you sought to accomplish and how you planned to do it.

Finally, the paragraph should end with a brief description of if you reached your goal and how successful you were in filling in that gap.

As a summary of your introduction:

And there we are on the basics of an introduction. More posts on introductions will come in the future with more detail and advanced techniques, though if yours manages to hit these points, it will be a good introduction to your work!

Happy writing!

Side note – Future blog directions

There will be more to come about introductions, including breakdowns of published introductions and how to avoid common pitfalls….plus tons of other posts I have swimming around in my head and need to get into posts!

But, since blogging time isn’t exactly in large supply lately, I want to know everyone’s preferences for future posts, especially since I’m getting some varied requests…

Some requests:

-Video blog posts

-Examples/formulas

-Download-able guides

Are there specific paper sections you are still stuck on?

Basically, what do YOU want to see more of? What do YOU want to see less of?