Phew, Marie Curie postdoc fellowship applications were finally submitted almost two weeks ago now, and I just now feel like I am catching my breath!

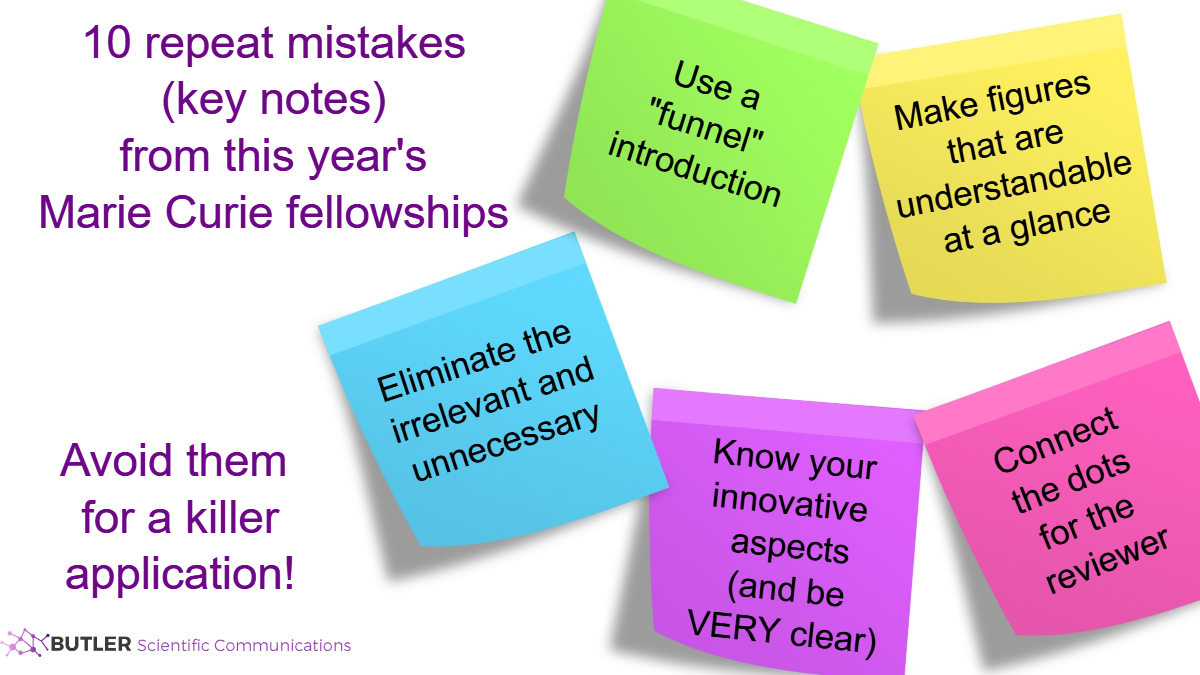

I had more applications to work on this year than ever before, so a lot of the repeating patterns really stood out…which means I get to tell you guys my key notes to give your future applications a boost!

None of these tips will be specific for the Marie Curie and will apply to nearly any grant, so don’t let the source stop you from getting something useful here.

So without further ado…what I noticed from this year’s batch of Marie Curie applications:

1) Answer the question that is asked

Even if you think this goes without saying, keep reading – it is more nuanced than you think!

The Marie Curie Individual Fellowship (MCIF) is pretty famous for having a lot of very specific questions that need to be answered, and sometimes the differences between these questions are not always clear.

Therefore,

- read the template – it lists everything you need for each essay in detail

- answer every single one of the trigger questions asked in the template to help you address the overall essay

- check if there are similar essays and decide how you will split up what you want to say

If you don’t know what to write, the template will spell it out for you. Answer everything it is asking.

To help your reviewer, you can include part of the wording from the template when you answer your question. This is especially useful for multi-part questions, as it will draw attention to your answer to show them that you are clearly addressing what they are specifically looking for.

Ex:

When the essay asks for the multidisciplinary aspects of the project, you can answer with “The multidisciplinary aspects are…” to show the reviewer exactly where to look.

This works the same for “Broader Impacts” in NSF applications! “The broader impacts of this research include…”

2) Answer ONLY what is asked

Building from point 1, answer ONLY the question that is asked. Just because you have extra space in an essay does not mean an aside about your previous research successes is appropriate.

At best, the reviewer will ignore it as they search for only the specific information they need. At worst, they will read it and be annoyed, and you will seem unable to follow directions and disorganized.

3) Be SPECIFIC

When discussing any aspect of your project, vagueness is a killer.

Not only does it sound like you yourself might not know what you are talking about, it is also much less captivating for a reader.

Vague = Boring.

Therefore, remove any vague terms in your application and replace them with specific words or descriptions that will better capture what you wanted to say anyways.

You never need terms like “very” and “a lot”. Just delete them and save the space!

Never say “new” or “novel”. If anything, this is the “first application of XX technology in mice”.

Never use “significant” unless you are discussing statistics, and when you are, give the p-value.

This isn’t “under-represented”, instead “less than 1% of commercial kits contain this…”

Also try to replace anything like “more reliable”, “better suited”, etc, and instead tell the reader WHY that is the case. It will get you much further in convincing a reviewer of the importance and innovation of your work.

4) Know your innovative aspects

That leads us right into point number 4.

Be clear on what points in your proposal are innovative and make sure they are explicitly stated in writing. I actually highly recommend having an entire subsection called “innovative aspects” or something similar and numerically listing the innovations with a brief description of each.

If you aren’t clear on your innovative aspects, they most certainly won’t come across to the reader.

Even when you ARE clear on these innovative aspects, though, if you don’t explicitly write them in the proposal, they will also likely be missed by the reader anyways.

5) Use a “funnel” introduction

Even more than in a manuscript, your space is limited in a grant.

Therefore, even more than in a manuscript, your introduction should not be a literature review.

Instead, work out from your proposal to the overall problem in the field to decide how much you need to introduce to the reader. By working backwards, you can start at your proposal and add what the reader needs to understand it and how it fits into the overall problem you are addressing (the highest point).

Try to keep your intro to the following major points:

- What is the major problem to be addressed (THE GAP) and why is it important?

- What does the field look like? Are there currently existing solutions, what is the current best solution, and what are its the limitations?

- What background should the reader know to understand my work? Explain specific techniques you are proposing to use.

- What is my hypothesis, and what are my major objectives? How will this address the gap?

You only need to make a line from your research to the problem, and all side branches will be distracting. Keep it simple and to the point.

This has the added benefit of allowing you the space to BE SPECIFIC in the explanations you do decide to include.

6) Connect the dots for the reader

Even though something seems obvious to you, it might not be for your reader, so you always need to be connecting the dots.

This is going to be very important in the introductory material, as you will need to tell the reader where all of the facts you are giving them fit into the puzzle, and it will also be important in your research plan and essays as you have to move from point to point.

For example, if you are discussing a past experiment, tell the reader exactly why you are. Is it describing the current state of the field? Highlighting a problem? Shedding light on an interesting technique?

Never leave a fact hanging! Always integrate it with the rest of what the reader already knows by that point in the proposal.

7) Eliminate the irrelevant/unnecessary

I know that you want to tell your reader everything you know about this project to make it convincing, but excess information often backfires by diluting your overall message.

Be very stringent in what is included in your proposal.

Do you need to use two different words to say the same thing, regardless of if they are interchangeable in the field? Likely no. Pick one and stick to it.

Do you need to discuss the details of previous research, or is it enough to tell that research on the topic has been done and this is what they found? Likely all you need is the outcome and a citation.

Does an exhaustive list of the functions of your protein of interest need to be given, or can you recap for the reader only the ones relevant for the proposal?

You want to keep a laser focus in your proposal to ensure you grab and hold your reader’s attention the entire way through.

Think of your proposal like a page-turning thriller. There is no room for side stories or distractions if you want to keep the reader’s undivided attention.

8) Make your points clearly, but avoid excessive repetition

Along the same lines as point #7, remove the extraneous information, including any repetitions of previously discussed details. In MC applications, I see this often between the different essays – if you discuss a point clearly in one essay, there is no need to bring it up again in a different one.

The same can be said of the research proposal, as well. If you have sufficiently described a point earlier, refer a reader to it later instead of repeating the same information.

There is one exception here – for the major points you want to make, such as your innovative aspects, point these out wherever applicable. Try to use different phrasing each time, though definitely always highlight the innovative aspects and how your work addresses the gap in the field whenever this is relevant.

9) Make sure figures are understandable at a glance

Your figures are there to enhance your proposal and make certain aspects of it easier for your reviewer to understand. Therefore, these figures must be understandable at a glance, and cannot require your reviewer to study them and the caption for some minutes to get this information.

Figures that are hugely complex with lots of moving parts will require the reviewer to take extra time to try to figure out what the point of the figure is, and most reviewers don’t have the extra time to try to discern what you are trying to convey.

Think in terms of simplified cartoons and schematics, or data that is very basic and where it is easy to see the point immediately.

Therefore, make sure your figures:

- Do not require extensive text to understand (ie., a reader can mostly “get it” even without caption)

- Have a few word labels where necessary to clear up any confusion

- Include attention-shifters, like arrows, to demonstrate how to follow them

- Are as simple as possible – anything not completely necessary is removed

- Provide relevant information for your reader

Additionally, your reviewer can’t be expected to be an expert in all of the possible assays or data display techniques you might use. Therefore, if you have preliminary data in your figures, consider adding interpretations of the data directly to the figure, such as labels like “Increasing affinity —>” to show the reader that as the points move to the right, for example, the affinity is improving.

The actual data in the figure is not as important as what it shows the reader, so make sure that a reader can see exactly what your figure is showing as soon as they look at a figure – using words, arrows, cartoons, etc. whenever possible.

10) Have a visually appealing layout

Finally, your reviewer is likely reading what will seem like 1 million research proposals.

That means nothing will feel worse than opening up your proposal to see unending blocks of solid text.

Be nice to your reviewer and make it easier for them to find the information they need in your proposal using organization and an appealing layout.

Consider:

- Always use numbered section headings

- Use bold and italics (and even rare phrases in a different color) to draw attention to key points

- Use figures to break up big blocks of text

- Make appealing line spacing where possible, including before new sections or between paragraphs if you have sufficient space (even 2 pt space between paragraphs makes it easier to read!)

- When listing items, do not write in paragraph form. Use bullet points or in-text numbering (ie, “(i), (ii), etc.”)

Basically, when you are editing your proposal, if it looks daunting for you to edit, it will definitely be daunting for your reviewer to read. Fix it.

Overall, when writing any type of grant, it is important to remember that your reviewer is likely (i) not an expert in your field and (ii) has too many proposals to review to give adequate attention to any of them. Therefore, it is your responsibility to make sure your entire proposal is easily understood by a non-expert and that it is organized in such a way that it is easy for your reviewer to find the key information they are looking for.

How was your last grant?

Which of the above points do you already do? What point will you make sure you do next time?